Ancient Asia — Oswald Spengler

An essay from the Spengler Estate. Published in the journal "Die Welt als Geschichte," Vol. 2, 1936, Issue 4, W. Kohlhammer Publishing, Stuttgart.

Tasks and Methods

The plan for this book is based on the idea that it should open a series of works addressing historical issues in Asia. Consequently, I believe it is appropriate not to summarize the previous results here, as that will have to be left to the subsequent writings, but to develop the entire complex of partially or not yet solved questions, new methods, surprising perspectives, and goals, so that future research can at least overview the field in broad outlines. Therefore, I will set aside my own opinions to highlight the significance of the many prevailing opinions.

A. The first chapter would present the primitive culture of ancient Asia. The concepts of antiquity, the Middle Ages, and modern times completely vanish from the western horizon. In this era, some major cultural circles begin to clarify slowly.

1. The primordial Nordic stretch from Scandinavia to Korea, which has long emerged in the Indo-European and Altaic issues and whose internal unity will probably prove to be greater than currently believed. Once one goes beyond the language changes, racial transformations, and geographical shifts of ethnic names to internal cultural forms, a lasting and pronounced unity emerges from the finds, graves, ornaments, and customs.

2. The Southeast circle: Extending from central China and Burma to Polynesia, and equally bound to the sea as the first is to the inland. Here, questions of prehistoric sea routes to East Africa (Madagascar, via South Arabia) and America (Peru, Guanacaste) arise, which relate to ocean currents and trade winds. We also approach the moment when Indian research, which has so far been limited to philology and literary analysis, can and must compare its results with the layers of finds from the Stone and Bronze Ages. Only then would Indian history of the 2nd millennium BCE be placed on a solid and probably entirely new foundation.

3. The West circle, encompassing the areas from the Nile to the Indus and, it seems, showing a significant unity in the 4th millennium that begins to shed light on a common southern origin of Egyptian and Babylonian cultures.

In all three circles, the ancient, eternal trade routes must be investigated, partly along the coasts (origin of seafaring), and partly through the large clearings of inland forests and mountains (origin of the wheel). These routes first emerge as trade routes primarily for metals, amber, and precious weapons; once discovered and put to use, they also guide the migrations of peoples, which must proceed cautiously to avoid the dangers of starvation or getting lost.

B. By the end of the 4th millennium, the two earliest high cultures on the Nile and Euphrates begin, probably on a common Stone Age foundation with a developmental direction that seems to have an enduring effect from the south towards the Mediterranean and Black Seas. From the end of the 3rd millennium, the diffusion of mature forms (myth, astronomy, technology, economy, weaponry, art?) along the old trade routes becomes noticeable, certainly both towards the Sudan and the high north and east.

C. With the aging of these two cultures, all of Asia enters a period of powerful upheavals around the middle of the 2nd millennium. A major movement occurs from the northern circle to the south:

The horse; the entirely new mobility of small warrior tribes; a passion for adventure, chivalry, and a worldview of a ruling class that simultaneously develops into grand forms in the old clans, Indo-Iranian knighthood, and Homeric heroism.

1. In the Western world, the omnipotence of the two oldest cultures disappears during the Kassite and Hyksos periods; sea peoples, conquerors with Indian Mitanni names; collapse of the Anatolian states, the Minoan empire. New kinds of wars and war objectives: a upheaval like the migrations of peoples on the ruins of the Roman Empire.

2. In the south, the same event at the same time: the invasion of the Vedic tribes into the already Bronze Age Dravidian world.

3. In the east, the Zhou period begins in a small area of northern China, with events closely related to those of the other two. The Zhou also come from deep inland; with them, the feudal era begins. I consider the entire alleged history of China before 1500 to be a later construct. The "imperial dynasties" with real names of rulers were undoubtedly transformed into a sequence of dynasties from coexisting ruling houses, as in Babylon and Egypt.

D. These similar developments need to be traced down to around 300 BCE. However, there remains the bridge of the Central Asian-Scythian population; many dark questions about the fate of this vast region from the Danube to the Amur and Brahmaputra. What races? What languages? What changing summaries into ethnic groups? Scythians, Cimmerians (Tatars?), Tocharians, Huns?

E. Since the 4th century BCE, the three great civilizations, widely radiating and equally receptive to foreign influences (image of Hellenistic, Indian, Chinese metropolises). There is a predominance of the west-east direction.

1. The late antique world flooding the ruins of ancient Egypt and Babylon; Alexander; Gandhara art, Hellenistic empires in Bactria; creation of the plastic Buddha type. Effects reaching into China.

2. On Syrian-Arabian soil, the new culture of magical style, with ethnic forms of religious imprint and a touch of Hellenistic character. Spread of Christian, Jewish, Manichean, Mazdean teachings and peoples (both as a unit!) primarily eastwards; repeatedly the old great burial road of the Nordic Stone Age, along which the Chinese emperors build their great wall, which the Roman emperors continued in Europe. The old northern circle is thereby isolated for centuries.

3. In accordance with Hellenism, a less plastic and optical than soft-rhythmic wave of forms from India under the leadership of Buddhism. Influence of Indian ornamentation, also spiritual, on the east and southeast as far as Japan and Java.

4. At the same time, a diffusion of Chinese civilization from the Huang He basin across the Yangtze to Polynesia, with traces possibly into the interior of the Americas.

5. But now a counter wave: The Chinese empire proves to be stronger than the Roman one. Along the Stone Age burial road, people from the northern circle attempt to break into the rich worlds of the south. The Altaic-Germanic migration of peoples initiated by the Huns, having been repelled at the borders of China, moves westwards and breaks through the boundary wall of the Roman world. The intrusion of more primitive forms and views into the Sassanian Empire (already the Parthians?), into Byzantium, and finally in a broad wave through the Germanic tribes mixed with Asians into Spain and Morocco. The movement is partially prepared by magical religious propaganda (Manichaeans in southern France, Montanists in North Africa, Arians through the Ostrogoths by the Don into Italy). The inseparability of Germanic and Central Asian form in the so-called migration art, as well as the internal affinity of wooden architecture from Scandinavia and Russia to northern China and Korea. These are the ancient forms of the northern circle.

F. Conclusion. In the far west, a new culture builds upon the results of the migration of peoples. In the Near East, the conclusion of the magical culture through the summarizing force of Islam in its final form of the 8th and 9th centuries. New tremendous religious storms, which carry Islam to Spain, the Sudan, India, and China and largely absorb the older religions into it. Conclusion in the Caliphate.

As the last major event that shaped today's image of Asia, the Mongol invasion under Genghis Khan, an event probably preceded by similar ones for millennia, of which we only recognize the effects, not the causes (Cimmerians, Central Asian tribes that set the Indo-Aryans and Mycenaean peoples in motion?). The Mongol invasion brings Mongol rule to India, foreign dynasties to East Asia, sultanates in the west, and khanates in Russia. Asia becomes definitively a region littered with cultural ruins under changing rulers, while in the far west, a major historical event is being prepared.

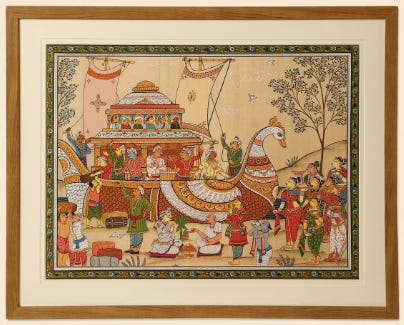

This overview only makes sense in the planned concise form if all individual questions are addressed in the following volumes and illuminated from the state of our knowledge. Here too, the individual problems must be clarified through a small, careful selection of images and maps.