France and Europe — Oswald Spengler

A 1922 essay by Spengler arguing that France’s desires to establish control over the Ruhr region and create a Confederation of the Rhine under its protection as well as expand into Africa.

The fact that currently dominates the global situation is the astonishing rise of France to an unquestionably leading power. On the continent, it has no more rivals. England, through a clever strategy that oscillates between persuasion and threats, is being placed in service of French plans. American wishes are coolly dismissed, and others aren't even acknowledged.

The French people, with their 39 million, march at the bottom of the great nations. They have been experiencing a low birth rate for decades. Mentally, they are very old, very refined, and very worn out. Politically, they have also aged. For 50 years, they have nurtured only one thought: retribution for a lost war. Others have organized colonial empires, created industries, and built a world of social institutions. France, however, in 1894 staged the cult of Joan of Arc as a symbol of military retribution. "We French will conquer nothing more," Zola told a visitor at the time. And now? A nation that was on the path to settling down like the Spanish after glorious centuries, a nation saved only by Anglo-Saxon bayonets and billions, today plays with the fate of these powers. It has forgotten, and the world with it, who ultimately forced victory. It has forgotten the hundreds of thousands of foreign dead in its trenches. It is convinced that it alone has won and thus claims the right to even greater successes.

For today, France is the only country whose ruling circles are always driven first by ambition—the ambition awakened by Robespierre and Danton and trained by Napoleon on the grandest scale—to place their foot on the necks of foreign nations. This tradition, which tolerates no contradiction, will always prefer loud glory to material advantage, the enjoyment of military triumphs to economic prudence, and a splendid moment to a less brilliant but significant future. France misjudges the seriousness of its own social and economic intentions. France is the only country that, since the Battle of Marengo, is ready to accept even the bitterest hardships, even a bloody civil war, as a consequence of its desire to continue exercising power in some way. The Frenchman of the 18th century, of the Rococo, died out with the victories of the Jacobin armies.

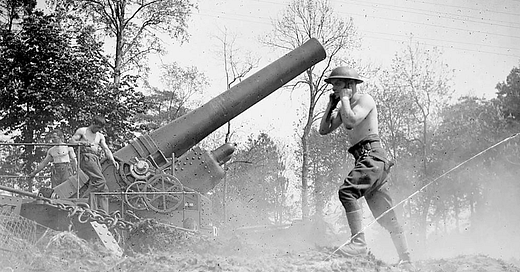

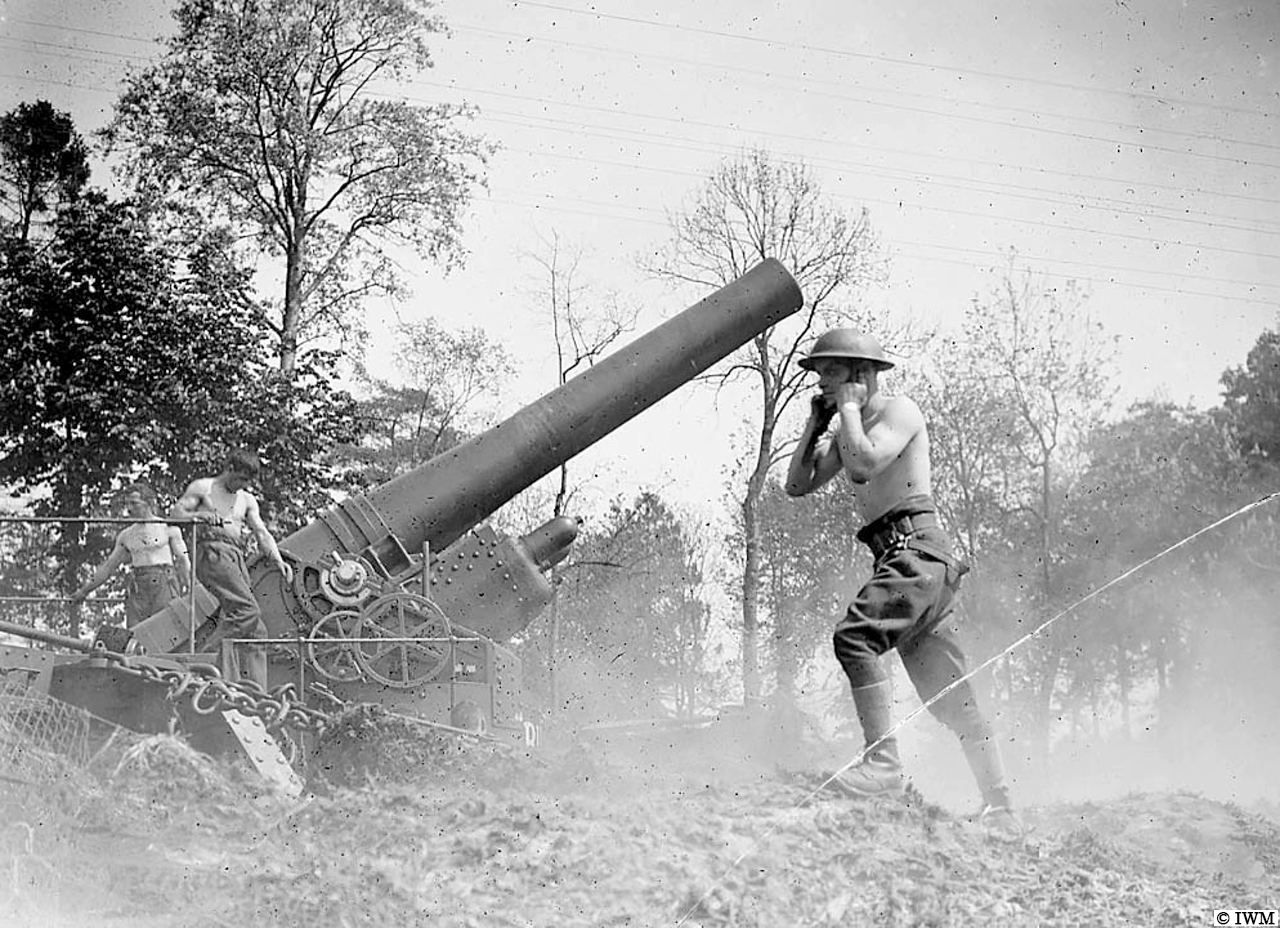

It is beyond the limits of the French character, and even more so beyond the limits of French taste, to allow conquered lands to flourish, to make yesterday's enemies into tomorrow's friends. In Africa and Indochina, the French are the worst colonizers imaginable. From the wars of Louis XIV, which laid a desert belt along the Rhine, to the mistreatment of European peoples by Napoleon's armies, which eventually led to the downfall of his empire, the French sense of victory has always remained the same. No nation, except for the Russians, has fought its revolutions with such boundless destructive fury and terrible bloodshed. Think of the systematic depopulation of the Vendée since 1792, the destruction of Lyon in 1793, and the burning of Paris's public buildings in 1871. Today, a frenzy of this kind again fills large circles of the people, who, against all expectations, have risen to the forefront of events.

And as with everything in them, their character, spirit, ambition, and expressions of power are old, so too are the current goals of this power. The entire policy is increasingly clearly a revival of Napoleonic plans. These 39 million want to be the masters of Europe and the world. What was in 1919 still a very vague urge under the impact of a sudden and unexpected success is today a plan pursued with all the clarity and energy of the French spirit. One watches with astonishment as the Rhine line is fortified, before which Germany is to lie in ruins, perhaps in the form of a Confederation of the Rhine, while the Ruhr region, as an outer fort, is to control access to the North Sea, the Little Entente the land bridge along the Danube to the Orient, and the vast possessions in Northwest Africa are to cover the route to the Nile, while air and submarine weapons secure the sea side.

Since the success in the Ruhr, which could not fail against a completely disarmed and ruined country if it remained isolated, the next opponent has been clearly identified. It is about a push against the Anglo-Saxon world, and thus a triumph of the Romanic over the Germanic world. It is in history as it is in business: with success, the ally of yesterday becomes the opponent of tomorrow. The outcome of the French elections next spring may determine the fate of the world. The current chamber emerged from a specific hope. If success on the Rhine and in the Ruhr is definitively secured, which is where all the energy of French politics is focused today, then the new elections will create a chamber of loud triumph and thus the center of a decidedly aggressive policy. This chamber will be strictly bound by the votes of its electorate in this direction, and it will similarly bind its leaders. For let there be no mistake: if the French nation, at the moment of such expectations, entrusts power to a man, it does so with an unequivocal command. Napoleon I knew very well that the first step backward on the path of military glory meant the end of his rule. That is why, since the retreat from Moscow, he was no longer able to engage in serious peace negotiations, as were repeatedly initiated since 1813 and 1814. He openly told Prince Metternich this in Dresden in September 1813. For the same reason, the Bourbons needed the war in Spain in 1816, and the Orléans in 1832 the one in Algeria. And when Napoleon III ascended the throne with the slogan "The Empire is peace," he also knew that the Second Empire would mean war if it was to sustain itself. The expedition to Mexico in 1861 occurred only because there was no prospect of a major war in Europe at the time. When Boulanger was on the verge of a coup d'état in 1886, it was primarily the announcement of war against Germany that secured his supporters' prospects. For the same reason, new elections, if they take place under the impression of a great political success, will mean war for France, and indeed, as a consequence of global political developments since 1918, war against English world dominance.

France has made it clear today that what it seeks from Germany is not primarily money, but control over the Ruhr and, beyond that, the establishment of a Confederation of the Rhine under French protection. This is a necessary step along the old Napoleonic path. The Ruhr region is precisely where Napoleon founded the Grand Duchy of Berg in 1806, which he handed over to his brother-in-law Murat, leaving no doubt about its military purposes from the start. In the following year, the Kingdom of Westphalia was established to the northeast, governed entirely by the French and whose troops became part of the French army. Furthermore, in 1810, the German North Sea coast was finally annexed by France. As early as the summer of 1923, the nationalist magazine *Vie Maritime*, associated with the French naval circles, called for the occupation of Bremen and Hamburg, and this idea has been increasingly expressed since then. There are no means in the utterly defenseless Germany to prevent the sudden occupation of the North Sea ports and their establishment as impregnable bases for French air squadrons and submarines. The significance of holding this coast for threatening England’s east coast is well known today. This would enable the Continental Blockade of 1806 to be reinstated at any moment, but with all the offensive means of modern naval and aerial warfare, and based on all the lessons learned about the effects of such a blockade. The distance from the Ruhr region to the mouths of the Ems and Weser rivers is 200 kilometers. This represents less than two days for a modern strike force equipped with automobiles and accompanied by cavalry. Germany has no interest in making significant sacrifices of its own and with no prospect of success to prevent a French attack that does not directly affect Germany but does not want to be, as before, the battleground of an Anglo-French war—alongside Holland, which in 1809 already saw an English expedition land for the same reason—and does not want the impoverished, desperate, and jobless population along the Rhine and Ruhr to be mass-recruited into the French Foreign Legion, which is being vigorously promoted under the protection of the Versailles Treaty to form the core of a white army in Africa. The immense contiguous French holdings in northwest Africa represent the new factor that Napoleon did not encounter during his expedition to Egypt and that today allows a repeat of his advance with better prospects. A new Fashoda is being prepared here. Since Germany was excluded from Africa, it has had no interest in power distribution there. But it watches with growing concern as all of Europe is threatened from there by a black army numbering in the millions. France is conducting forced conscription on a large scale in the Sudan. It is training the Negro in modern military tactics and teaching him to reflect on the limits of the power of white populations. Unlike the Germanic, the French sense of race does not oppose equality with blacks. General Mangin publicly declared—so loudly that it could be heard in Africa—that France militarily represents a nation of not 40 but 100 million people, and Colonial Minister Sarraut similarly publicly referred to the Negroes as “frères de couleur,” colored brothers. It is well known that there is no aversion to mixed marriages in France. This army of black Frenchmen is already, whenever it wants, the master of Africa. The French government has just approved the construction of the Sahara Railway, which has no economic but purely strategic significance, linking the Sudan with its vast human resources closely to Morocco and Algeria. The exploitation of the rich mineral resources already allows the extensive production of war materials on African soil. The rapprochement of Italy and Spain in this regard comes too late, and moreover, France, as the owner of the hinterland, is in a position at any moment to close the Mediterranean by occupying Tangier and thereby putting Italy in a very difficult situation by cutting off coal and food supplies. A new push towards the Nile is being prepared, but with an army that faces no equivalent in Africa, and with deployment lines from West Africa that cannot be endangered at all. The fate of India will be decided at the Nile. Napoleon knew this already.

And a third point: The increasingly open attempts to break up western and southern Germany into a series of dependent territories also correspond to a Napoleonic idea: a land bridge along the Danube to the Orient. This would completely encircle the Mediterranean from north and south and subject the entire Near East with all its access points to French control. In pursuit of this goal, Napoleon married the South German princes into his family. Today, France supports every movement there, whether communist or monarchist, that offers a chance to break up Germany. What is called Yugoslavia today was then the Illyrian Provinces. Then, as now, their purpose was to cut off Italy, dominate the Adriatic Sea, and keep Vienna in check. The final, equally old goal is an understanding with Russia, whose leaders will undoubtedly prefer an alliance with the strongest power in Western Europe to a conflict with it. This would be the northern route to India, which the Soviet Republic would open more willingly than Tsar Alexander I once did.

And now the economic-technical side: In 1923, France produced 5.3 million tons of iron ore, England only 1 million, and Germany 0.77 million. Combined with the Ruhr region, France controls 35% of Europe’s coal production. If we add Belgium and the Little Entente, particularly Poland, which today, as under Napoleon, is nothing but a French province whose military and industrial resources Paris can freely dispose of, no less than 60% of Europe’s coal production is on the French side, compared to England’s 25% and Germany’s 4%, noting that even the remaining Silesian mines are constantly threatened by Poland, and we should not forget that the reserves of the mines on the continent will last 800 years at pre-war production levels, while England’s will last barely 150 years. The same is true for petroleum. This means that France has the largest arms industry and by far the largest raw material reserves in Europe.

This is the situation in Europe during the “Age of Reparations,” and it makes no sense to treat the reparations issue today as a problem of compensation for damages caused by the party blamed for the war in the peace treaty. Certainly, there is talk in Paris of the need to balance the budget, but this budget has been thrown off balance primarily because revenues have been consumed for ever-expanding militaristic purposes. Under the armistice and the Treaty of Versailles, Germany has given up over 2 billion pounds in various forms, not including the material value of its territorial losses. This includes the enormous costs of the occupation of the Rhine and the dismantling of war material and transport means. But with the sums that Germany was forced to pay in cash under English pressure, France built its air fleet. The German Saar coal, with which France is making lucrative deals in Italy, Belgium, and Switzerland—it has set up sales offices for German coal everywhere—has enabled further army reinforcements and the granting of armament loans amounting to hundreds of millions of francs to the Little Entente. Every new billion means new air squadrons, submarines, and African regiments.

If the purpose of these payments were the restoration of the French economy, it would be incomprehensible why France seeks a German revolution with all its economic consequences. But France needs such a revolution to gain a free flank and a theater of operations in Central Europe for its further goals through the disintegration of Central Europe. The communist movement is advised by Russia and supported by France for very different reasons, but undoubtedly with the intention of achieving the same result. Moreover, as the Fuchs trial in Munich recently taught, there is no movement, whether communist or monarchist, whether that of the separatists on the Rhine or the Poles in Upper Silesia, to which France does not offer money whenever there is any hope of reshaping Germany according to French wishes.

Historians are always amazed at how little people learn from historical experiences, how even leading statesmen only recognize the goals of others once they are achieved. This allowed Napoleon’s rise, as well as Japan’s rise to the leading world power in the East. France is already in a position where it need not fear any equal opponent. In two years, it may have no opponent left who still thinks of resisting. And while this world domination, without internal preparation or justification, can only be an episode, it may yet force an era of relentless wars and plunge Europe, Africa, and Asia into chaos before it collapses. The defeat of the Revolution and Napoleon cost 20 years, 2 million lives, and billions in national wealth. The defeat of European-African France, which has resumed this role, may demand sacrifices that Europe may no longer be able to bear.