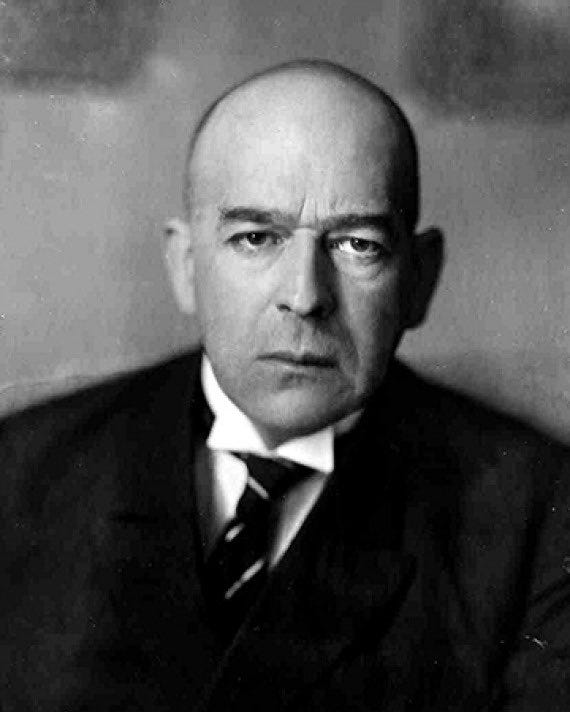

Heraclitus: A Study on the Energetic Fundamental Concept of His Philosophy — Oswald Spengler

The first English translation of Spengler's doctoral dissertation on Heraclitus

Introduction

In the Ionian philosopher Heraclitus, Greek philosophy of the 6th and 5th centuries reaches its peak—not as a school but as a series of independent, powerful thinkers who were far more mature and astonishingly creative than their time. These thinkers, unlike any who came after when philosophy moved to Athens, left an indelible mark. Greece has never produced greater individuals than these, who, following one another, created a cosmic vision not through critical analysis or strict scientific methods, but with high intuition and a profound perspective that encompassed the meaning of the world, its past, and its future. This is the context in which their achievements should be assessed. Rather than the cool precision of differentiation and dissection found in Aristotle, we find here, to use Goethe's phrase, the "exact sensory imagination"—a focus on forms and ideas, not on abstract conclusions, concepts, and laws. Heraclitus stands out as not only the deepest but also the most versatile and comprehensive spirit among them. The systems of Anaximander, Xenophanes, and Pythagoras share similarities with his. The great problems of Greek thought—such as the relationship between form and the thing-in-itself, the concept of law, the idea of the inner unity of all being or events, the origin of being, and the origin of difference—discovered during this time and condensed into naive and bold formulas, were unified in the fundamental ideas of his teachings, while others represented them individually.

It would be incorrect to see Heraclitus as a successor or imitator of these teachings. Whether there was a relationship of master to disciple between Anaximander or Xenophanes and him, or another closer connection—unlikely considering the intellectual and political independence of the Hellenic cities and the self-confident, unconventional lifestyles of these philosophers—is a question of little importance. The possibility of indirect influence exists. However, only those numerous potential stimuli from observations, experiences, impressions, and opinions of others would have worked if they met similar, already present elements. Heraclitus's independence has never been questioned, which can be confidently inferred from his character. If a similar direction in the thinking of those philosophers can be observed (like the similarity of starting points and parallel treatment of similar questions), it results from the organic unity of intellectual life within a defined cultural epoch, as history often shows (e.g., the ἀταραξία as the basis of all ethical teachings in the 3rd century, the problem of method in Bacon, Descartes, Galileo).

The idea in which Heraclitus presented a new conception of cosmic existence is an energetic one: that of a pure (immaterial), lawful process. The distance of this idea from the views of others, including the Ionians, Eleatics, and Atomists, is extraordinary. Heraclitus remained completely isolated with this idea among the Greeks; there is no second conception of this kind. All other systems contain the concept of a substantial basis (ἀρχή, ἄπειρον, τὸ πλέον, ὕλη, τὸ πλῆρες, and even Plato's world of appearances, γένεσις in contrast to the world of ideas, αἰτία τῆς γενέσεως), and the Stoics, who later appropriated Heraclitus's words and formulas, had to infuse them with a Democritean spirit to make them acceptable to the age. This, above all, explains the frequent misunderstandings in the interpretation of his doctrine—not because it is insufficiently known to us1, but because it stands in contrast to the thought processes familiar to us. The history of Heraclitus's scholarship shows how, in an attempt to assimilate a difficult, foreign thought, one resorts to all possible other ideas due to the lack of an appropriate modern exposition of the idea to cling to familiar concepts and views. One may doubt whether any of the possible explanations have yet to be attempted. Heraclitus appears as a disciple of Anaximander (Lassalle, Gomperz), Xenophanes (Teichmüller), the Persians (Lassalle, Gladisch), the Egyptians (Tannery, Teichmüller), the Mysteries (Pfleiderer), as a Hylozoist (Zeller), Empiricist and Sensualist (Schuster), "Theologian" (Tannery), as a forerunner of Hegel (Lassalle). His great thought is like the soul of Hamlet: everyone understands it, but each in their way.

The attempt to judge the ideas of a philosopher who was unfamiliar with the precise, well-practiced language of a highly developed science without this precision does not lead to the goal. Teichmüller (vol. I, p. 80) says: "Anyone who seeks exact concepts in Heraclitus is making a useless effort. In Heraclitus, philosophy consisted only in an allegorical generalization of some striking facts. If we wanted to define it more precisely, we would destroy Heraclitus's way of thinking." This viewpoint leads to severe errors due to inadequate determination of concepts and untenable analogies. One example is the application of the concept of ἀρχή, created by Anaximander for his philosophy and meaningful only within Hylozoism, to others, including Heraclitus, in whose system it is entirely irrelevant. We must be cautious, even skeptical, not only in explaining Greek thought elements themselves but especially in distinguishing them from modern ones. We must not forget that our fundamental concepts are the result of the entire development of modern philosophy since the 16th century and have absolute validity only within this framework of ideas. Thoughts that emerged within such different cultures, like ancient and modern, which already differ in their understanding of the essence of science, correspond to entirely unique concepts. Even a seemingly obvious concept like matter is not the same for Democritus and in modern natural science; for example, the cause of motion in Democritus lies in the nature of matter (τύχη), whereas in modern science, it is an independent factor, energy associated with the ether, outside of matter itself.

Another difficulty is that although Heraclitus was sure of his views, he did not always express them adequately in language. The lack of a scientific language with purposefully created expressions, and the absence of a proper polemic among these philosophers, which would have forced a sharp and careful mode of expression, are not the main reasons for this. The crucial reason is the impossibility of conveying a new understanding of nature, contrary to appearances, using familiar word symbols formed under different impressions and opinions. Goethe, whose views on nature were carried by a similar spirit, recognized this limitation well. "All languages arise from immediate human needs, occupations, and general human feelings and perceptions. When a higher person gains an intuition and insight into the secret workings of nature, their inherited language is insufficient to express something entirely removed from human things. They must always resort to human expressions in their view of unusual natural relationships, often falling short, lowering their subject, or even damaging and destroying it." (Eckermann, Conversations with Goethe III, June 20, 1831).

A comprehensive presentation of Heraclitus's entire doctrine has become impossible due to the loss of his writings. Here, only a development of the principle that this thinker made the foundation of his worldview will be attempted, which can be summed up in a few words: πάντα ῥεῖ, the idea of a pure lawful becoming. It follows from these words that the explanation must proceed in two directions: the becoming itself and its law. This separation is purely methodological. It must be emphasized that this does not correspond to a dualistic structure of the Heraclitean cosmos. All the thoughts mentioned below are the same fundamental principle, conceived as a unity, preserved only in a number of different representations as they arose from the imagination of a passionate artistic person, whether in the fragments or perhaps even in Heraclitus's book, given his aphoristic writing style.

It would be a hindrance to understanding this doctrine if we had lost knowledge of the great and tragic personality of Heraclitus. Without this understanding, we could not grasp why this philosopher made the ἀγών, the foremost custom of his time, the custom of the cosmos, or what he meant by the fire to which he attributed a dominant role in the universe. His doctrine is unusually personal for that time and for a Greek, despite the fact that he did not often speak of himself.

We see a man whose entire feeling and thinking were dominated by an unbridled aristocratic inclination, strongly ingrained by birth and upbringing, and heightened by resistance and disappointment. Here lies the fundamental reason for every aspect of his life and every peculiarity of his thoughts. Even in the energetic concentration of his system, in the avoidance and disdain of all details and trivial matters, and in writing in short, strong phrases familiar only to him, we recognize the hand of the aristocrat.

The Hellenic nobility2, whose decline was occurring during this time, created the most significant and beautiful period of Hellenic culture. It established the type of the perfect Hellene, an incomparably high and noble culture of the individual (καλοκαγαθία); it represented not only rights or interests but also a worldview and a custom (as noted by Burckhardt). It was a proud, happy, power-loving, and power-accustomed caste, proud of its blood, rank, weapons, and "antibanausia"; it held a monopoly on spirit and art. One can understand the enormous ethical power of this caste and its worldview over the individual's mind. Though the caste itself might decline, anyone who once stood under its influence could not escape it. Heraclitus possessed all its self-awareness and pride, an intense, involuntary nobility foreign to any self-reflection; he passionately adhered to its brave, healthy, joyful customs, to struggle, and to the pursuit of glory.3 This proud, unyielding man loved the distinction between rulers and the ruled; he had reverence for the ancient customs and institutions4, which were no longer sacred to democracy. He was too deep a judge of humanity to judge the people of his time simply by birth and rank. He believed in the Homeric distinction5 between the ἄριστοι, people of great and noble life views, and the masses (οἱ πολλοί), whose shortcomings he discerned with a sharp, mocking eye.6 He did not engage in attacks and disputes with the δῆμος; his taste and self-control, one of the first virtues of a noble Greek, forbade it.7 Without rage or outbursts, he judged the people from above, coldly, maliciously, with contempt and disgust, sometimes hiding his rising resentment with a sarcastic remark.

The name "the weeping philosopher," which antiquity gave him, did not arise without reason, as anecdotes8 and some of his aphorisms9 reveal a bitter, wounded tone. Tied by birth and deep attachment to an ideal of life, he was born at a time when this ideal could no longer exist. The power and customs of the nobility had declined or disappeared, and democracy began to rule. He was too stubborn and defiant to submit or uselessly complain. One of the first and most influential offices in Ephesus, which fell to him by hereditary right (that of βασιλεύς), was no longer what it should have been. He renounced it. The life of the πόλις lost its aristocratic form, and the masses began to govern.

He then left the city, where he could have been a minor ruler, and went into the mountains, into voluntary solitude, a life that seemed the most terrible to the sociable Greek, who was intertwined with the fate of his city. He remained there, unforgiving, enduring his life, which eventually, if we believe Theophrastus, brought him close to madness.10

For the Hellenes, fame—or one might say notoriety—was the highest goal.11 It raises the question of whether this self-imposed solitude and the strange traits that attracted admiring attention might have compensated for a role in Ephesus. Every Greek wanted to be known by everyone, at any cost. Herostratus is a famous example of what one might attempt for this purpose. But this is also seen in Alcibiades, Themistocles, and any other who can be considered a true Hellene. One must not forget this national form of ambition in Heraclitus, a fatal trait of the Greek character. This quality, which appears ignoble in our eyes, was not a pursuit that denied the opponent magnanimity and recognition but rather an unbridled, consuming envy—even hatred—against anyone who was more fortunate, a tormenting awareness of being less admired than others, which made the Greeks, with their vivid sensibilities, a profoundly unhappy people.

As a result, philosophy never developed into the treatment of a problem by a succession of thinkers over time. Each began anew, often from the opposite standpoint, with few gratefully accepting the discoveries of their predecessors. Instead, they emphasized the differences, sometimes exaggeratedly, and until Aristotle, each of the great philosophers looked down on the others with enough mockery. One should not expect Heraclitus, as a Greek, to acknowledge the merits of others. On the contrary, he tended to emphasize contradictions sharply in paradoxes and antitheses, and when he mentioned a famous name, it was always with a certain malice. The peculiarity of his fate increased his self-awareness as an extraordinary person and led to an overemphasis on originality, a fundamental rejection of all foreign opinions, and even the avoidance of common phrases that might have sounded trivial to him. Under these circumstances, the genesis of his thoughts should be traced, and the degree of their dependence on contemporary systems should be assessed.

For every thinking person, there exists a mode of thought that, arising from the same psychological causes as their worldview and the results of their thinking, is closely connected with them. In the broadest sense, not only as an instinctive method of logical reasoning but also as an unconscious method of selecting and evaluating impressions of all kinds, it serves as an intermediary between personality and system, sometimes even as an independent source of valuable ideas. The style of thinking and the doctrine itself are related. This circumstance is important for Heraclitean philosophy. Heraclitus was fortunate to be able to draw freely from his desires in a time of naive thinking, which had not yet matured to reflect on itself, without being limited to smaller-scale research within established directions by significant prior work in his field. This is a fortune that Goethe was aware of when he once emphasized: "When I was eighteen, Germany was also only eighteen." (Eckermann, Conversations with Goethe I, February 15, 1824.)

If Heraclitus was an aristocrat in his worldview, he can be called a psychologist concerning his entire method of thinking. Both are often observed to be related. This does not imply anything about the subject matter of his investigations but suggests a method of treatment. He does not consider nature as an object in itself, in terms of appearance, origin, and purpose; instead, his method is an analysis of natural processes insofar as they are processes, changes, according to their lawful relationships. His system can be called a psychology of world events. From this new philosophical approach comes the discovery of new problems. Heraclitus can be considered the first social philosopher, the first epistemologist, and the first psychologist. His aphorisms about humans are not ethical sayings like the maxims of Bias or Solon, but are truly observed, entirely objective remarks, avoiding a didactic tone.

Finally, let us not forget a fundamental difference that distinguishes Heraclitus and all Greek philosophy from modern philosophy. The people, whose educators were gymnastics, music, and Homer, who invented the word "κόσμος" (cosmos) for the world because they saw in it above all the sense of order and beauty, did not treat philosophy as a science (abstract scientific investigations were always subordinated to the metaphysical ultimate purpose) but as a way to create a worldview that allowed them to understand their place in the universe and as an opportunity to express their joy in shaping. It would be wrong to consider Greek thought, which emerged under the open sky, in a southern, sunny landscape, from a cheerful and lively life, as inferior to ours because of this unfamiliar closeness to art. For the Hellenes of the classical period, philosophy is formative art, the architecture of thoughts. The Hellenic plastic power, their ability to subject everything learned and self-created to a unified style, is immense. This feeling for form gives rise to the tendency to conceive philosophical systems as works of art.

Heraclitus is the most significant artist among the Presocratics. This is evidenced not only by the rich and colorful pathos of his style but especially by the ingenious plasticity of his presentation. He perceives his ideas; he does not calculate them. The intuitive nature of his thought, entirely foreign to dialectic reasoning12—such as that which underpins the opposing system of Parmenides—is supported by his always aptly chosen examples (such as those of the bow and the lyre, the mixed drink), in which he attempts to depict a tangible image before him. Sometimes, this was the only means of communication left to him, as his approach to linguistic expression posed challenges he could not always overcome, despite a strength of thought rarely found in ancient philosophy. His main idea completely contradicts appearances and habitual thinking and requires a high degree of abstraction to even be discovered. An unwavering consistency and a clear view over the field of his investigations give him an internal unity of the system, which probably has never been reached again. It is focused with great simplicity on one idea and is unassailable in its details due to its inherent logic.

Heraclitus can be described as a realist, despite the ease with which he might be mistaken for the opposite. Every concept that seems to suggest symbolic intentions can, upon closer examination, be traced back to a real basis. He has a thoroughly healthy perception of tangible realities13 and often demonstrates great subtlety in distinguishing.14 Yet, he never denies the aristocrat; his thinking has a true imperial style, employing a very summary approach, even for that time.15 Only the great, fundamental ideas are worth considering to him, with a pronounced aversion to genuinely scientific detailed research. He has a specific, strictly limited view of how one should think: one should not want to know everything, only what is valuable and great; select little, but penetrate it thoroughly. He desires depth, substance, clarity, not breadth of knowledge. Hence his polemic: "polymathy does not teach insight; it would have taught Hesiod, Pythagoras, Xenophanes, and Hecataeus" (Fr. 40). "Mathiê" is merely the acquisition of knowledge about things. The accumulation of facts without overview and understanding is abhorrent to him. It is not about knowing little: "For one must indeed be very knowledgeable in many things to be a philosopher, according to Heraclitus" (Fr. 35). "Historíê" is the deep, critical observation (not knowledge from books, as Gomperz notes in the aforementioned work, p. 1002 f.; "histor" means witness, critic, and in Homer, arbiter. See Porphyry, "De abstinentia," II, 49: "The true philosopher is a witness of many things").

A "scientific philosophy" will never arise on such a basis. However, one must distinguish between the questions lying outside the core focus and the fundamental idea itself, which is indeed exhaustively elaborated. One should not measure the logic of the thought process by the unsystematic presentation. The work is a collection of aphorisms, as a remark by Theophrastus and the fragments themselves teach. Heraclitus did not attempt to be didactic in the most modest sense, let alone popular; this is evidenced by his style, which does not consider ease of understanding, and perfectly aligns with his contemptuous worldview.

Pure Movement

I. First formulation: "Everything flows."

Cosmos as an Energy Process

The fundamental idea on which Heraclitus based his view of the cosmos is fully contained in the now-famous phrase "πάντα ῥεῖ" ("everything flows"). However, the mere concept of flowing (or change) is too vague to reveal the finer and deeper gradations of this idea, whose value does not lie in merely asserting the variety of successive states of the visible and tangible world, something no one doubts. At the outset, it is important to highlight the significant difference between the concept Heraclitus had of the course and inner character of the world process itself, which he said is not accessible to our perception, and the appearance that the world of things presents to us, which we must logically understand as the manifestation of this process and its effect on the senses. By adopting this Kantian distinction, which Heraclitus' doctrine undoubtedly contains in practice, even though it does not appear fundamentally separated in the fragments of his writings, one avoids one of the most common misconceptions in evaluating this doctrine.

If one wants to trace the occurrences in nature back to their most fundamental elements, the concept of change remains open to multiple interpretations. One might assume a substrate with the sole determination of persistence; in this case, change appears as the manner in which the persistent exists at every moment. From this cautious and unassailable standpoint, Kant described the proposition that substance persists as tautological. "For this persistence alone is the reason why we apply the category of substance to appearance, and one would have to prove that there is something persistent in all appearances, of which the changeable is nothing but a determination of its existence."16 To arrive at a simple and intuitive conception, one usually adds to that characteristic of the substrate the attributes of spatial occupation, impenetrability, and qualitative constancy, thus obtaining the concept of (physically conceived) matter, whereby its change can only be conceived spatially. This Democritean concept of the displacement of mass parts (περιφορά), which modern natural science also contains, is not found in "πάντα ῥεῖ." It is possible to dispense with the concept of a substrate altogether, whether as the persistent in the change of appearances (which can be described physically as the invariant ratio of forces acting on a body to the resulting accelerations) or as actual matter, whereby the concept of change (becoming, flowing) gains a new and richer content.

The most general basic concepts essential for the schematic illustration of natural processes, which every thinking person tends to, undergo a development over the centuries determined by the contemporary standpoint of science, so that they fully satisfy the thinking of a limited period only in content but are so necessary to it that it is not easy to free oneself from their influence to correctly and objectively grasp the differently natured concepts of an earlier epoch (in this case, Heraclitus'). When Plato in the Philebus explains the world of appearances as a product of empty space (τὸ μὴ ὄν, ἄπειρον) and mathematical form (πέρας), it is hardly possible for us to form the corresponding conception of these concepts.

Most attempts to understand Heraclitus' particular trains of thought are influenced by the view peculiar to modern natural science and many philosophers since Hobbes—not merely as a "working hypothesis" (Ostwald)—which almost necessarily divides what is given in perception into an active and a passive component. Thus, two quantities are distinguished here, matter and the independent, separate energy, whose object is matter. The second concept, unknown to Greek philosophy, must be understood as entirely substantial. As a result, the need to imagine a carrier to which this energy is bound is so strong that after its principal separation from matter, the wave theory of light led to the assumption of a second kind of matter, ether, simply because one could not imagine a quantity with these characteristics acting without a carrier. (Lord Kelvin has shown that this hypothetical ether, with properties as presupposed by the wave motion of light rays, is not viable.)

A physical carrier of movement is not necessary for the concept of action in space, the "reality." The energetic theory proposed by Mach and Ostwald is much closer to Heraclitus' idea. After the critical philosophers of the 18th century had already declared things to be coordinated complexes of sensations and thereby almost demonstrated the ultimate goal of all philosophical research, the comprehension of things in themselves, as impossible and erroneous, substance could no longer be conceived materially. Energetics recognizes this critique at least for the concept of matter and defines nature as a sum of energies (although this concept is again conceived entirely substantially). "We gain our knowledge of the external world only through the specific stimulation of our sensory organs by the objects of the same; we attribute the nature and strength of these stimulations to the 'properties' of matter. However, if we take away those properties from the objects, we are left with nothing accessible to our experiences, and matter disappears when we try to think of it by itself" (Ostwald, Chem. Energie, 2nd ed., p. 5). This approach of energetics to Heraclitus is important because it makes it possible for the first time to bring his thoughts into a modern, scientific form. What exists in space is exclusively energy: "If we think of its various forms apart from matter, nothing remains, not even the space it occupied. Thus, matter is nothing but a spatially coordinated group of different energies, and everything we want to say about it, we say only about these energies" (Ostwald, overcoming scientific materialism, p. 28). However, this substance can again be applied to the aforementioned determination by Kant that it itself persists (J.R. Mayer's law) and only its way of existing changes (the "forms" of energy, light, heat, electricity).

The Greek view is different from the outset. The concept of force was only created by Galileo and was unknown to the Greeks. Therefore, we must distinguish between motion and energy. Motion (a relational concept) presupposes only something moving and nothing else. Energy (the substantively conceived cause of motion) is itself a second quantity alongside the moving object, even if this again is to be thought of only as a group of energies. We say: "The force acts at a point." In contrast, monistic Greek philosophy knows only immanent and ideal causes of motion (ἀνάγκη, φιλία καὶ νεῖκος, λόγος, τύχη); Democritus' atoms move due to τύχη; it is in their nature to move. They need no acting energy. For Greek monism, the substance present in space (best described by Parmenides as τὸ πλέον, the space-filling) as a single and indivisible substance has become an entirely different concept. It is this concept of substance that Heraclitus denies.

The first problem of Greek philosophy, for which myth left a gap but also gave no direction, is that of the "origin" of things. The chaos at the beginning of the world, which a Greek would have defined as a qualitatively indeterminate, irregularly moving mass, gave rise to the idea of a primal substance. Ἀρχή is a substance. According to Thales and Anaximenes, the world consists of the qualitative transformations of this initially existing substance. Anaximander's significance lies in his elimination of sensory qualities for its determination. The ἄπειρον, thought of as ἀρχή, is something entirely removed from perception, whose specific effect on the senses first produces qualities and thus things. Still, a physically conceived background of sensations is assumed here. Absolute skepticism toward the concept of substance is difficult. Parmenides rightly observed that all thinking relates to being, that everything thought of at that moment acquires the property of substantiality.

Since Greek thought knows no separation of moving and moved, and Heraclitus explicitly emphasizes unity in world events—his saying ἐκ πάντων ἓν καὶ ἐξ ἑνὸς πάντα is equivalent to Xenophanes' ἓν καὶ πᾶν—the assumption of a pure, unified, continuous "becoming," which the Eleatics deny17, must exclude the concept of substance in every sense.

In the execution of the idea, the utmost difficulties of linguistic expression arise; one of those cases where we notice that language itself contains philosophical principles. Our entire philosophy is a correction of language usage, remarked Lichtenberg; "thus, true philosophy will always be taught with the language of the false." We cannot precisely express the denial of being linguistically. Οὐδὲν μένει, πάντα χωρεῖ: one feels that the subjects of these sentences already contain a substantive being. Language is Eleatic philosophy.

Heraclitus fundamentally declares things to be undergoing change in every sense: λέγει που Ἡ., ὅτι πάντα χωρεῖ καὶ οὐδὲν μένει. (Plato, Cratyl. 402 A.) This complete transformation (μεταβολή in Fr. 91, ἀνταμοιβή in Fr. 90) Plato (Theaetetus 181 B. ff.) divides into spatial (περιφορά) and qualitative (ἀλλοίωσις) change. It must be emphasized that for a Greek, there is only one real entity in the external world to find the rejection of the concept of substance in this thought. Heraclitus never uses the concept of substance, which must have been familiar to him from the philosophy of the time (ἀρχή, ἄπειρον) (Teichmüller Vol. I p. 147). He also does not know the concept of empty space, easily following from the assumption of moving matter. Heraclitus attempted to find an appropriate expression for his new idea. In the statements: συνάψιες ὅλα καὶ οὐκ ὅλα, συμφερόμενον διαφερόμενον, συνᾶιδον διᾶιδον, καὶ ἐκ πάντων ἓν καὶ ἐξ ἑνὸς πάντα (Fr. 10) and: γνώμην, ὁτέη ἐκυβέρνησε πάντα διὰ πάντων (Fr. 41. Cf. Pseudo-Linus 13 Mullach: κατ᾽ ἔριν συνάπαντα κυβερνᾶται διὰ παντός), one undoubtedly sees the attempt of an energetic formula to express pure action in space, not bound to matter.

This action is beyond sensory perception. What we see and feel is always a being, a persistent state: "θάνατός (being, unmoved) ἐστιν, ὁκόσα ἐγερθέντες ὁρέομεν" (Fr. 21). The senses deceive: This insight made Heraclitus a skeptic of knowledge. The background of the physical world surrounding us, the "becoming" acting in space, is not recognizable. Heraclitus speaks of an invisible harmony compared to the visible one in the world of appearances (ἁρμονίη ἀφανὴς φανερῆς κρείττων Fr. 54). Fragment 123 expresses the same idea: "φύσις κρύπτεσθαι φιλεῖ,"18 nature loves to hide; the deeper nature is not immediately discernible, one must first interpret the impression of the senses. Additionally, the appearance of the energetic process for us is diverse: "ὁ θεὸς ... (=φύσις, κόσμος) ἀλλοιοῦται δὲ ὅκωσπερ [πῦρ], ὁπόταν συμμιγῆι θυώμασιν, ὀνομάζεται καθ᾽ ἡδονὴν ἑκάστου" (Fr. 67).

From this theory, it necessarily follows that becoming and flowing must be uninterrupted: "ὁ κυκεὼν διίσταται [μὴ] κινούμενος" (Fr. 125). This image of the potion is an example of the mastery with which Heraclitus can give his ideas a vivid clarity. (Nietzsche draws attention to the aptness of the expression "reality.") A balance of antagonistic action would mean eternal rest. It is essential for the existence of the cosmos that different tensions constantly oppose each other, resist, and measure themselves against each other; no moment of rest must occur; there must always be a minimum of imbalance present in space.19 We must think of the eternal action as the swelling and diminishing of tensions (oppositions). An attempt to express this is Fr. 91: "ἀλλ᾽ ὀξύτητι καὶ τάχει μεταβολῆς σκίδνησι καὶ πάλιν συνάγει καὶ πρόσεισι καὶ ἄπεισι." For this thought, the almost synonymous expressions "συμφερόμενον διαφερόμενον" (in Fr. 10: "συνάψιες ὅλα καὶ οὐκ ὅλα, συμφερόμενον διαφερόμενον, συνᾶιδον διᾶιδον κτλ ... Plato Soph. 242 e: διαφερόμενον ἀεὶ ξυμφέρεται. Luc. vit. auct. 14: αἰὼν παῖς ἐστι παίζων πεσσεύων συνδιαφερόμενος." Plato Symp. 187 A: τὸ ἓν γάρ φησι διαφερόμενον αὐτὸ αὑτῷ ξυμφέρεσθαι) and "ὁδὸς ἄνω κάτω" (in Fr. 60: ὁδὸς ἄνω κάτω μία καὶ ὡυτή. Diog. Laert. IX, 8: καλεῖσθαι μεταβολὴν [vgl. Fr. 91] ὁδὸν ἄνω κάτω) are found. This notion, that the action in space, i.e., the swelling and diminishing of opposing tensions, occurs in such a way that a striving for equilibrium is always present, is known in energetics as Helm's law: Every form of energy tends to move from places where it is present in higher intensity to places of lower intensity (Helm, Theory of Energy, p. 59 ff.). The difference lies solely in Heraclitus' non-substantial conception. The attempt to give this abstract consideration a shape understandable and pleasing to the eye – a tendency Heraclitus most easily and gladly indulges in – ultimately leads to the notion of wave-like movement. (It is the only easily comprehensible concept of movement tied to place.) The Ionian, who daily gazed at the sea, had to know how much its movement, from the gently swung line to the high meandering waves, mirrors the restlessness of a strived-for and never-reached union. In this sense, half abstraction and half artistic vision, one may understand the "παλίντροπος ἁρμονίη κόσμου, ὅκωσπερ τόξου καὶ λύρης" (Fr. 51).20 The line of the ancient Greek bow is similar to that of the lyre (Arist. Rhet. III, 11 p. 1412 b 35: τόξον φόρμιγξ ἄχορδος), an evenly curved line whose ends approach each other. To get closer to Heraclitus' idea of the lines of opposing forces seeking equilibrium, one might think of the arsis and thesis of metrics and the melodic line of melodies. This avoids the error of assuming oscillating particles. This concept applies to the entire extent of the cosmos: "τὸ ἕν γάρ φησι διαφερόμενον αὐτὸ αὑτῷ ξυμφέρεσθαι ὥσπερ ἁρμονίαν τόξου καὶ λύρας" (Plato Symp. 187 A). A comparison allows the full significance of this idea to be seen: "ἣν (ἀνάγκην) εἱμαρμένην οἱ πολλοὶ καλοῦσιν, Ἐμπεδοκλῆς δὲ φιλίαν ὁμοῦ καὶ νεῖκος· Ἡ. δὲ παλίντροπον ἁρμονίην κόσμου ὅκωσπερ λύρας καὶ τόξου" (Plut. de anim. procr. 27 p. 1026). If one recalls what εἱμαρμένη, the great, everywhere and unconditionally prevailing fate, means to a Greek, one will also understand the meaning of Heraclitus' harmony (which is equivalent to λόγος or νόμος).

All these attempts to gain a new perspective on events arise from the denial of persistent being. Everything is not merely in flux—"everything" would still imply a being—but the background of appearance must be thought of solely as pure action, or if you will, as a sum of tensions.

The Fire

Heraclitus mentions fire in a way that forces us to think of it as a state of being. Thus, even for him, there are states in the world of appearances—essentially coinciding with the states of aggregation—that challenge explanation in this system where the concept of substance is rejected. The fact that there seem to be states of rest in nature (from which the assumption of persistent substances originally arose) cannot be denied. Heraclitus mentions these states (θάνατός ἐστιν, ὁκόσα ἐγερθέντες ὁρέομεν. Fr. 21) and attributes them to the deception of the senses. The eye is denied the ability to see becoming and flowing (Fr. 54 and 123. See p. 18). It appears to man under several typical forms, forms of sensory appearance (earth, fire, sea, whirlwind; these are already the elements of Empedocles), which are changing and of temporary existence. They have a purely subjective reality. Formerly, light, heat, and electricity were spoken of as natural forces. Today, they are similarly referred to as forms of energy, with the tacit assumption that they are to be considered as manifestations of "energy in itself," that unrecognizable cause of events. Heraclitus conceives fire, the sea, the earth, and the storm in this way—things that only seem to have being and duration, which they want to convince the discerning mind of, and which, removed from the eye, are nothing more than eternal restless flowing and becoming, one like the other.

Thus, the concept of fire is given: a manifestation of the cosmic process, but not yet its meaning. Heraclitus presents this natural phenomenon, which should have no precedence over others, in a mysterious way. Because of this high significance, one might believe that the main point of the whole doctrine has been found here; the idea contained in it has also been subject to many misunderstandings. The view of fire merely as a symbol of change21 can be dismissed; an obscuring symbolism is no longer attributed to this philosopher. But it is incomprehensible how the idea and designation of fire as ἀρχή could become customary with Aristotle.22 Ἀρχή is a very specific term, which due to many inseparable assumptions can only be applied in a limited way. The Ionians created it; it includes, if properly understood, the whole system of these philosophers. Above all, it contains the idea of development and transformation into a normal state. The Ionian question was: From what are things derived? A substance, both temporally and physically original, is assumed (for ἀρχή means both), which, according to Anaximander, takes on qualities while remaining itself. Despite qualitative variability, the ἀρχή has the conceptual features of a substance. According to Anaximenes, other states arise from air through a spatial (volumetric) change of this original substance (πύκνωσις, μάνωσις), a view that does not contradict that of Democritus. How could one associate Heraclitus with this problem? None of his statements relate to this question. Heraclitus does not know of a substance; that alone is decisive; he also does not know the idea of development from an original and normal state. It is impossible to ask about a primal substance in the context of his thoughts. His problem was: How does the cosmic process take place? The alleged states and substances are in reality the changing form of its appearance: πυρὸς τροπαὶ πρῶτον θάλασσα, θαλάσσης δὲ τὸ μὲν ἥμισυ γῆ, τὸ δὲ ἥμισυ πρηστήρ (Fr. 31). Thus, fire is not considered as a substance but as τροπή (ἀνταμοιβή in Fr. 90). This concept is valuable. Τροπή and ἀρχή are the strongest opposites; ἀρχή is a substance, something that exists in itself and persists, while τροπή is a metamorphosis, a form. As ἀρχή, only one of the existing substances can always be assumed, which is first present for some reason; the others depend on it. Τροπή is fire and any other appearance equally. One might wonder if Anaximander could have used this expression.

Heraclitus placed fire at the center of the equally legitimate types of appearance. The reason for this choice lies in the less scientific and more artistic character of his thinking. He was guided here by the same feeling that has made fire and the sun objects of religious veneration throughout history. This most mysterious, noble, and pure of all natural phenomena appeared to people of a distant time as something sacred, and Heraclitus's reverent and aesthetically impressionable nature was not immune to this impression. He saw here the character of the restless (πῦρ ἀείζωον) depicted most clearly. This suited his inclination for vividness. Fire is the most formidable and powerful of the elemental forces that truly govern nature. Therefore, he loved it (τὰ δὲ πάντα οἰακίζει κεραυνός Fr. 64. Πάντα γὰρ τὸ πῦρ ἐπελθὸν κρινεῖ καὶ καταλήψεται Fr. 66). No scientific reason for this preference can be found, and it is also unlikely that he wanted or could rely on such reasons.

The visible form of cosmic movement changes incessantly. Fire, as one of the possible forms (τροπαί), is, although the most beautiful and noble, not a more physically important or more original substance than a material substance, such as the ἀρχή. It is a form of appearance like any other, transient like any other: πυρὸς τε ἀνταμοιβὴ τὰ πάντα καὶ πῦρ ἁπάντων ὅκωσπερ χρυσοῦ χρήματα καὶ χρημάτων χρυσός Fr. 90). The τροπαί are in constant mutual replacement; this is one aspect of their nature. Heraclitus found a fortunate expression for this change of equivalent appearances: ζῆι πῦρ τὸν ἀέρος θάνατον καὶ ἀὴρ ζῆι τὸν πυρὸς θάνατον, ὕδωρ ζῆι τὸν γῆς θάνατον, γῆ τὸν ὕδατος (Fr. 76). One will understand the intention of this expression: The momentary dominance of one form already implies a power increase of the other, which ultimately reaches a degree that must bring about a change. In this context, fire is considered—again, not physically but aesthetically—the most perfect of imaginable forms. "According to Heraclitus, there is a gradation in the elements determined by their distance from the moving and self-living fire" (E. Rohde, Psyche II S. 146). The cosmos, the grand order of all world events, is in a certain sense really identical with fire (κόσμον τόνδε, τὸν αὐτὸν ἁπάντων οὔτε τις θεῶν οὔτε ἀνθρώπων ἐποίησε, ἀλλ᾽ ἦν αἰεὶ καὶ ἔστι καὶ ἔσται πῦρ ἀείζωον, ἁπτόμενον μέτρα καὶ ἀποσβεννύμενον μέτρα Fr. 30). In Heraclitus's opinion, the cosmos, the sublime nature, is fittingly and naturally represented by the most exalted, purest, and noblest form; thus, the cosmos is only in a state of perfection when the change assumes exclusively the form of fire, a state that regularly recurs over time (Fr. 30, 66). All other forms (solid, liquid, airy) appear inferior in comparison to the beauty and power of fire. (The words χρησμοσύνη and κόρος Fr. 65 point to this. Teichmüller [I S. 136 ff.] rightly sees here an allusion and variation of the Greek idea that appears in Aristotle's concept of entelechy, the process from potential to actual.)

"Everything flows" as a Formal Principle of Organic Nature

We come to the other, so to speak, external application of Heraclitus’s principle of change: the visible and tangible changes in nature that surround us. The fundamental idea contained in the formula "Everything flows" appears here as a formal principle of all forms of life and events. We must distinguish between the never-perceivable background of things, the actual process of becoming and acting, and its external appearance as the world of the senses. The application to the latter realm is the widely recognized and easily understandable one, most commonly associated with "everything flows."

Only the restlessness of the energetic process is invisible (as are, for example, the ether waves of light); the changes in the visible world are evident to everyone; they constitute what is popularly referred to as the "life of nature." The second distinction is more important. The natural processes lack the appearance of regularity, a strict, uniform rule. In the growth of a plant, the undulating motion of the surf, the course of atmospheric events, people do not usually perceive this impression. One cannot speak here of a uniform, or even an uninterrupted, change in all cases. In the energetic process, movement is logically necessary, even tautological; here it is possible, at most a rule. Before Heraclitus, no one had noticed a rule here. The simple appearance teaches that this life and process lack rhythm. Therefore, the artistic view of Heraclitus regards the harmony of appearance (which he still accepts) as less significant than the other, derived from a metric regularity, merely imagined (ἁρμονίη γὰρ ἀφανὴς φανερῆς κρείττων Fr. 54).

The transformation itself escapes no one; only its law is hidden. But it is there if one knows how to find it. And it is the same as that of eternal action.23 This is a profound thought. Heraclitus believed that nature is essentially under the impression of this change, which is also perfect and universal: ποταμῶι γὰρ οὐκ ἔστιν ἐμβῆναι δὶς τῶι αὐτῶι οὐδὲ θνητῆς οὐσίας δὶς ἅπτεσθαι κατὰ ἕξιν (Fr. 91). This thought has, as is typical of a general inclination towards Heraclitus, been subject to a moralizing interpretation that completely overturns the simple meaning. Schuster interprets it as "no thing in the world escapes complete destruction" (p. 201 f.), and Lassalle cites the verse24: "Everything that comes into being deserves to perish" (I, p. 374). This misunderstands the deepest aspect of the idea. Heraclitus wants to contradict a teleological view of being. He sees the "course of the world" as eternally the same, without beginning or end: κόσμον τὸν αὐτὸν ἁπάντων οὔτε τις θεῶν οὔτε ἀνθρώπων ἐποίησε, ἀλλ᾽ ἦν αἰεὶ καὶ ἕστιν καὶ ἔσται κτλ... (Fr. 30). The change of appearances is always the same, always repeating; this notion crystallized into a doctrine of eternal recurrence. Any attempt at a development idea, like that of Anaximander (biological), is entirely absent here, as is any reference to the concept of causality. There is no better image for this idea than the one Heraclitus himself chose: ποταμοῖσι τοῖσιν αὐτοῖς ἐμβαίνουσιν ἕτερα καὶ ἕτερα ὕδατα ἐπιῤῥεῖ (Fr. 12). We see the course of the world as if we were standing on the bank of a river; it continuously flows by, always the same, without beginning or end, without cause or goal. We can only understand the occurrence in the cosmos by its character, not as an event as a whole.

Heraclitus's view of life is a remarkable example of this idea: the river of generation flows so continuously that it never stands still.25 Instead of the individual living being, he considers the entire succession of a species as an individual, whose phases (the life of the individual) are merely moments and stages in a grand, uninterrupted metamorphosis. According to this more morphological than physiological perspective, life should be thought of as a change from youth and old age, from increase and decrease in strength (Ἄνθρωπος, ὅκως ἐν εὐφρόνῃ φάος, ἅπτεται ἀποσβέννυται according to Byw. Fr. 77, modified and elaborated by Diels). This idea makes the meaning of the phrase ζῆν τὸν θάνατον (to live is to die) clearer. In another saying: γενόμενοι ζώειν ἐθέλουσι μόρους τ᾽ἔχειν. μᾶλλον δὲ ἀναπαύεσθαι καὶ παῖδας καταλείπουσι μόρους γενέσθαι (Fr. 20), the term ἀναπαύεσθαι (to rest) is significant as it represents a pause between two periods of high activity, supporting this view.

A consequence of the constant change in the sensory world—which must logically be extended to the perceiving human—is skepticism about knowledge. Before Heraclitus, no one had seen this as a problem, and it is a testament to the great intellectual energy to have overcome the unconscious pride that a time in which philosophical thought is just emerging tends to rely upon. From the fundamental elements of this doctrine, a complete agnosticism could have developed, and Protagoras did indeed take this step. However, Heraclitus was too dynamic and positively inclined to let a denying attitude truly undermine his philosophy; he could not be mistrustful and rejecting in the main questions (as Lassalle might suggest through citing the Faust quote). The theory of knowledge is not among Heraclitus's primary concerns. It only gains attention in this context because it sharpens the main idea by demanding an insight into the restless, ever-changing nature of the world and overcoming the apparent. (Fr. 21: θάνατός ἐστιν ὁκόσα ἐγερθέντες ὁρέομεν: the external world appears to be at rest. Arist. Metaph. I, 6: ὡς αἰσθητῶν ἀεὶ ῥεόντων καὶ ἐπιστήμης περὶ αὐτῶν οὐκ οὔσης. This skepticism is directed only against a science that assumes permanent conditions. Fr. 107: κακοὶ μάρτυρες ἀνθρώποισιν ὀφθαλμοὶ καὶ ᾦτα βαρβάρους ψυχὰς ἐχόντων, i.e., for people who remain uncritical at mere sensory perception.)

All creations of culture—state, society, customs, and viewpoints—are products of nature; they are subject to the same conditions of existence as the others, under the strict law that nothing remains and everything changes. It is one of Heraclitus's greatest discoveries to have noticed this inner connection between culture and nature. The resistance and balancing of opposing tensions mean the same for energetic processes as war does for human existence. (Fr. 8: πάντα κατ᾽ ἔριν γίνεσθαι.) War justifies the aristocratic hierarchy that Heraclitus admired. There can be no eternal and lasting conditions; gods and humans, free and enslaved, are subject to the law of necessary change (Fr. 53). Heraclitus knew well that aristocracy in Greece had to decline.

In this chaos of transformations, there can be no lasting values; this is the ultimate consequence of such a view. This realization, against which the spirit resists the longest, was emphatically maintained by Heraclitus. We have before us a completely developed system of relativism. Indeed, where there is no stagnation and rest, the concepts of ethics and aesthetics can only apply to the individual and only be applied on a case-by-case basis. Thus, it is with evaluations of physical beauty (Fr. 82, 83), wisdom (ἀνὴρ νήπιος ἤκουσε πρὸς δαίμονος ὅκωσπερ παῖς πρὸς ἀνδρός Fr. 79), the precious, pleasant, and useful (ὄνους σύρματ᾽ ἂν ἑλέσθαι μᾶλλον ἢ χρυσόν Fr. 9; Fr. 37, 58, 61, 110–111). The values and qualities of things lie between two extremes and are only subject to subjective application.

The Formal Principle

The Idea of Form in General

The general, or rather the naive and more original conception of things focuses on grasping the substance and its inner nature. It is only through advanced analysis of the process of cognition that one learns that the world we perceive is a creation of the senses, and that the concept of substance (and energy) itself is a construct of our thinking. This highlights another element of appearance, namely form or mathematical relationship. One creates a picture of the inner structure of things through the concept of substance and the properties thought to be contained within it, aiming to fully explain natural processes. Once it is understood that it is impossible and even contradictory to unlock nature in this way, one may forgo providing a visible representation of its innermost nature. It then becomes natural to find the important and significant aspects of appearance in its mathematical measure, in its form relationships. It is even possible to completely determine natural phenomena numerically without adding a hypothesis about their "essence," and this exhausts everything that can be reliably determined through the study of the relationships between objects and the subject due to the limits of cognitive activity. (An example is Maxwell's electromagnetic theory of light, which is entirely specified by a set of differential equations.)

The Pythagoreans and Heraclitus discovered this valuable and fruitful aspect of appearance and subjected it to observation first. In this emphasis on the formal as opposed to the material, a significant distinction in the decomposition of the given in perception into its components must be noted. Materialistic natural science and most modern philosophers differentiate mass and energy as secondary quantities, like Descartes' substances and Spinoza's attributes. Heraclitus, most Greek philosophers, and also contemporary energetics distinguish between substance and form. Substance here is to be understood as the sum of everything that appears to us (mass + energy, if you will), whereas the sum of all natural laws is to be seen as "form." Aristotle similarly differentiated between ὕλη (hylē) and μορφή (morphē), while Heraclitus viewed "becoming" as the given and the λογος (logos) as its form. Substance is not divided into parts or functions; rather, besides this given entity, only its form, which is represented in a series of (numerical) relationships, is of interest.

There can be no doubt about the value of form in this sense. The lawful relationship is the only constant in natural processes. "If one could measure all sensory elements, one would say that the body consists in fulfilling certain equations that hold between the sensory elements. – These equations or relationships are thus the truly enduring aspects." (Mach, Principles of Thermodynamics, p. 423). The deeper thought penetrates nature, the more importance numbers gain over images. Form has an epistemic value. From this perspective, they learned to appreciate the Pythagoreans. Philolaus teaches: "And all things that are known have number. For nothing that is conceivable or knowable exists without it." (Stob. Ecl. 22, 7, p. 456.) For Heraclitus, whose inclinations went in different directions and whose taste admired especially the harmony of the world's processes, the aesthetic value of form—specifically, the rhythm of "becoming"—is considered.

Heraclitus identifies the concept of λόγος with μέτρον. This term does not refer to a force, let alone an intelligence, but rather to a relationship. This idea, which was lost in later Greek philosophy, has often been misunderstood due to the influence of Stoic, Christian-Hellenistic, and especially modern dualistic views. Modern dualism originates from Christian worldviews and has shaped the development of modern philosophy. It is natural that the belief in some form of world order influences the formation of metaphysical ideas. The Christian dichotomy of world-God, which dominated medieval natural philosophy, continued in a series of further dichotomies: thought and extension, intelligence and substance, matter and energy. Despite growing abstraction, the fundamental division remained the same.

The Greek perspective was influenced by a different worldview. The gods were not perceived as rulers but as friendly and helpful companions of humans, sharing virtues, weaknesses, pain, misfortune, passions, and fate. The concept of εἱμαρμένη was crucial for Greek philosophy. The εἱμαρμένη is entirely impersonal—never depicted in the visual arts—and represents an inexorable law, permanent and inescapable. While Greeks could speak of the gods with joy and satisfaction, they viewed εἱμαρμένη with quiet dread. This belief is reflected in Greek tragedy, which ultimately acknowledges this formidable power with resigned acceptance. This secret certainty—that ultimately something determines the course of events that is not human, does not have a soul, is not driven by will, reason, or feeling, and is not subject to supplication—found expression in the philosophical knowledge of ἀνάγκη (necessity) or λόγος, the absolute world law. Heraclitus's early insight into this notion, which he derived from this belief, was to recognize that there are no exceptions.

Before Socrates, no Greek philosopher knew of a personal god; θεός (theos) was a physical term in their language. For scientific insights into nature, Olympus was never considered. The Greeks knew only the visible world in which they lived, the cosmos, and nothing beyond it. There was no temptation to assume a substantial energy or world soul. The law lies in the world as a relationship, whether it is called θεός, λόγος, ἀνάγκη, or τύχη. It is important to note that all these terms for a norm and lawful cause of change stem directly from the concept of fate. The λόγος is the εἱμαρμένη, an immanent fate, not a personal cause. This was not misunderstood in antiquity: ἣν (= ἀνάγκην) εἱμαρμένην οἱ πολλοὶ καλοῦσιν· Ἐμπεδοκλῆς δὲ φιλίαν ὁμοῦ καὶ νεῖκος· Ἡ. δὲ παλίντροπον ἁρμονίην κόσμου ὅκωσπερ λύρας καὶ τόξου (Plutarch, De anima procr. 27, p. 1026).

Heraclitus conceived the world as pure movement. The λόγος is thus its rhythm, the measure of movement. In this system, which knows no persistent being, the appreciation of the metric is all the more relevant. The Greeks had a highly developed sensitivity to form, not limited to visual art but extending to all aspects of life, which occurred involuntarily within certain limits (this is the sense of καλοκἀγαθία, σωφροσύνη, αὐτάρκεια, and other similar ideals of Hellenic living). We perceive this whole culture today as a formal work of art. Heraclitus emphasized harmony in the struggle of opposites. This harmony is metric. Several sayings reflect this: Κόσμον τόνδε τὸν αὐτὸν ἁνάντων, οὔτε τις θεῶν οὔτε ἀνθρώπων ἐτοίησεν, ἀλλ᾽ ἦν αἰεὶ καὶ ἔστι καὶ ἔσται πῦρ αείζωον, ἁπτόμενον μέτρα καὶ ἀποσβεννύμενον μέτρα (Fr. 30). Ἥλιος γὰρ οὐκ ὑπερβήσεται μέτρα· εἰ δὲ μὴ, Ἐρινύες μιν Δίκης ἐπίκουροι ἐξευρήσουσιν (Fr. 94). Θάλασσα διαχέεται καὶ μετρέεται εἰς τὸν αὐτὸν λόγον ὁκοῖος πρόσθεν ἦν ἢ γενέσθαι γῆ (Fr. 31). It is evident that every kind of cosmic process contains a μέτρον. It is likely that the repeated mention of Δίκη (Dike) emphasizes the strict regularity of this relationship. For Heraclitus, the value of the mathematical form of natural processes is very high.

It is also worth considering the relationship between Heraclitus’s idea and the corresponding Pythagorean thought. Pythagoras himself, of whom nothing certain is known and who is generally assumed not to have been a writer, is mentioned by Heraclitus only for his scientific method. A relationship of dependence can never be proven. It is also unlikely and unimportant. The actual parallelism between both systems is of interest. The earliest Pythagoreanism begins with the observation of mathematical relationships in all forms and processes of nature. Number theory is a later consequence of this fact. They start from the distinction between substance and form (ἄπειρον-πέρας), very much in line with Heraclitus (τὰ πάντα, κόσμος - λόγος, μέτρον). A passage from Philolaus makes this parallelism clear: Ἀνάγκα τὰ ἐόντα εἶμεν πάντα ἢ περαίνοντα ἢ ἄπειρα ἢ περαίνοντά τε καὶ ἄπειρα· - ἐπεὶ τοίνυν φαίνεται οὔτ᾽ ἐκ περαινόντων πάντων ἐόντα οὔτ᾽ ἐξ ἀπείρων πάντων, δῆλόν τ᾽ ἄρα, ὅτι ἐκ περαινόντων τε καὶ ἀτείρων ὅ τε κόσμος καὶ τὰ ἐν αὐτῷ συναρμόχθη (harmonically ordered). The similarity of the views is recognizable, but the specific formulation is individual. The formal aspect of Philolaus, which is to be understood as the geometric-arithmetic determinability of things, is something quite different from Heraclitus’s μέτρον, which is to be seen as the measure of movement through time. The problem itself is a generally Hellenic one; the specific formulation is decidedly individual.

The Idea of Unity and Necessity

The idea of lawfulness within nature was a novel concept. Heraclitus went further, finding that a single law governs all processes in their entirety. Xenophanes had also identified the idea of an inner unity of the world and made it the focal point of his teaching. His concept of ἓν καὶ πᾶν (one and all) denoted a unity of being in the absolute sense, without specifying its content. This is fundamentally different and less precise. Xenophanes does not recognize any norm, form, or quality of being, only the world and "God" as one. His unity is both qualitative and conceptual, a very general and pantheistic idea.

For Heraclitus, who did not assume a substance, this determination can only relate to the form of the energetic process, and to assume it as consistent and regulated. The major difference is clear. Heraclitus' idea is concretely defined and clearly presented; the unity is that of the λόγος (Logos) within the movement. All changes occurring in the cosmos are subject to the same rule. We find the effects of the same eternal law in the invisible becoming, in visible nature, in life, and in culture. The law of eternal recurrence is the same on a grand scale as the cycle of life and death and the upheavals of states, customs, and cultural conditions on a smaller scale. Therefore, Heraclitus calls λόγος (Fr. 2) and πόλεμος (Fr. 80) ξυνός (common) (see also ἓν τὸ σοφόν, Fr. 32). Here again, the harmony, based on the assumption of a common rhythm in all processes, should be noted. From this assumption, which contains a common rule for all events and thus excludes any end of the world, follows the congruence of all physical, ethical, social, and other laws, as well as their necessity and logical consequence. The statement: τρέφονται γὰρ πάντες οἱ ἀνθρώπειοι νόμοι ὑπὸ ἑνὸς τοῦ θείου (Fr. 114) can be seen as proof of these far-reaching implications. All conditions and factors on which the life of individuals and entire communities depend are the same laws of the cosmos prevailing here in another form, thus equally absolute, unavoidable, and resistant to any attempt to escape them—a profound and fearsome realization fitting for this unyielding and courageous personality. There is a strong fatalism in this view. This does not contradict the Hellenic sentiment; the εἱμαρμένη (fate) is the only dogma that none of their thinkers questioned. The Greeks liked to imagine this εἱμαρμένη, which like a storm cloud silently looms over humans and gods, sending down unexpected and devastating lightning bolts at any moment, with a secret pleasure in the terrifying. This gave rise to tragedy. One can indeed have no better concept of the law governing the cosmos than by comparing it to the fate, for instance, that governs the life of Oedipus. Invisible and unavoidable, it has a silent, yet all the more impressive presence. In the idea of the Logos, Heraclitus' conviction of the existence of εἱμαρμένη (fate) is deeply ingrained in his doctrine. It is likely that he used the term εἱμαρμένη directly for λόγος (Logos). In any case, they are the same, as one sees; the equivalence of both terms was generally recognized: Ἡ. οὐσίαν εἱμαρμένης ἀπεφήνατο λόγον τὸν διὰ οὐσίας τῆς τοῦ παντὸς διήκοντα· αὕτη δ᾽ἐστὶ τὸ αἰθέριον σῶμα, σπέρμα τῆς τοῦ παντὸς γενέσεως· καὶ περιόδου μέτρον τετραγμένης· πάντα δὲ καθ᾽ εἱμαρμένη, τὴν δ᾽αὐτὴν ὑπάρχειν καὶ ἀνάγκην· γράφει γοῦν· Ἔστι γὰρ εἱμαρμένη πάντως (Stob. Ecl. I, 5 p. 178).26 Similarly, Diogenes Laertius notes about his doctrine: πάντα τε γίνεσθαι καθ᾽ εἱμαρμένην (IX, 7) and: τοῦτο (= τροπαί) δὲ γίνεσθαι καθ᾽ εἱμαρμένην (IX, 8). Finally, the term is mentioned three times as Heraclitean by Aëtius (Diels Anhang B. 8). It is therefore very likely that Heraclitus also used the term for the corresponding idea. This equivalence of λόγος (Logos) with εἱμαρμένη (fate) must make it impossible to view λόγος as a personal or at least intellectual principle. Any conceivable intelligence, whether conceived as a god, world soul, or something else, is already subordinated to εἱμαρμένη. This aligns with the Hellenic belief that places fate unequivocally at the top. In this system, there is no room for even the slightest chance. Hesiod, who believed in the foreboding of certain days, drew Heraclitus' scorn, who viewed the belief in mysterious "powers" as naïve (Fr. 57). According to his conviction, any possibility of deviating from the lawful course of events is inconceivable.

Heraclitus' worldview, taken as a whole, appears as a grandly conceived poetry, a tragedy of the cosmos, on par with the powerful majesty of Aeschylus' tragedies. Among Greek philosophers, possibly excluding Plato, he is the most significant poet. The thought of an eternally ongoing and never-ending struggle that constitutes the content of life in the cosmos, where an imperative law governs and maintains a harmonious equilibrium, is a high creation of Greek art, to which this thinker was much closer than to actual natural science. A final thought, in which he surveys the world and delights in the effortless, innocent, and pain-free aspect of its becoming and acting, has survived: αἰὼν παῖς ἐστι παίζων πεσσεύων παιδὸς ἡ βασιληΐη.27

The opinion of Th. Gomperz is referenced from the Vienna Proceedings, volume 113 (1886), page 947. The other writings used here include:

Schleiermacher, Herakleitos der Dunkle (Works III, Part II, Vol.)

Zeller, Philosophie der Griechen Vol. I

F. Lassalle, Die Philosophie Herakleitos des Dunklen von Ephesos

P. Schuster, Heraklit von Ephesus

E. Pfleiderer, Die Philosophie des Heraklit von Ephesus

G. Teichmüller, Neue Studien zur Geschichte der Begriffe Vol. I, II

G. Schäfer, Die Philosophie des Heraklit von Ephesus und die moderne Heraklitforschung

G. Tannery, Rév. philos. 1883, XVI, Héraclite et le concept de Logos

For information on the nobility, refer to:

Wachsmuth, "Hellenische Alterthümer," Volume I, pages 347 and following.

J. Burckhardt, "Griechische Kulturgeschichte," Volume I, pages 171 and following, and Volume IV, pages 86 and following.

Fr. 24: "Ἀρηιφάτους θεοὶ τιμῶσι καὶ ἄνθρωποι."

"Warriors killed in battle are honored by both gods and men."

Fr. 25: "Μόροι γὰρ μέζονες μέζονας μοίρας λαγχάνουσι."

"Greater destinies receive greater fates."

These fragments are numbered according to the collection by H. Diels in "Herakleitos von Ephesus," Greek and German, Berlin 1901. This numbering is also maintained in the edition of the Presocratics by H. Diels (5th edition, Berlin 1934, edited by W. Kranz, text and translation pp. 150 ff.). [Publisher's note.]

Fr. 33: "Νόμος καὶ βουλῇ πείθεσθαι ἑνός."

"Law and the will of one should be obeyed."

Fr. 44: "Μάχεσθαι χρὴ τὸν δῆμον ὑπὲρ τοῦ νόμου ὅκωσπερ τείχεος."

"The people must fight for their law as if for a city wall."

The term "ἄριστος" (meaning "the best" or "noble") in the sense of nobility appears in Homer in the following instances:

Iliad II, 159, 327; VII, 193

Odyssey I, 245 and frequently elsewhere

Similarly, it is found in Heraclitus:

Fragments 13, 29, 49, 104

The term "οἱ πολλοί" (meaning "the many" or "the masses") is used in:

Fragments 2, 17, 29

Fr. 29: "Αἱρεῦνται γὰρ ἓν ἀντὶ ἁνάντων οἱ ἄριστοι, κλέος ἀέναον θνητῶν, οἱ δὲ πολλοὶ κεκόρηνται ὅκωσπερ κτήνεα."

"The best choose one thing over all, eternal fame among mortals; but the many are satiated like cattle."

Fr. 104: "Δήμων ἀοιδοῖσι πείθονται καὶ διδασκάλωι χρείωνται ὁμίλωι..."

"The people listen to singers and make use of a crowd as their teacher..."

Fr. 43: "Ὕβριν χρὴ σβεννύναι μᾶλλον ἢ πυρκαΐην."

Translation: "It is better to extinguish hubris (arrogance) than a fire."

Fr. 47.

He was once watching children playing when some people from Ephesus passed by and stopped. He snapped at them, "What are you staring at? Isn't this better than governing the state with you?" (Diogenes Laertius, IX, 3).

Fr. 121.

Fr. 85: "Θυμῶι μάχεσθαι χαλεπόν· ὃ γὰρ ἂν θέληι, ψυχῆς ὠνεῖται."

Translation: "It is difficult to fight against anger; for whatever it desires, it buys at the cost of the soul."

From the strong impression that this man made on his contemporaries arose well-known stories, such as the one that he deposited his writings in the Temple of Artemis, so that they would only come into the hands of future generations (Diogenes Laertius, IX, 6).

Fr. 24: "Ἀρηιφάτους θεοὶ τιμῶσι καὶ ἄνθρωποι."

"Warriors killed in battle are honored by both gods and men."

Fr. 25: "Μόροι γὰρ μέζονες μέζονας μοίρας λαγχάνουσι."

"Greater destinies receive greater fates."

Fr. 29: "Αἱρεῦνται γὰρ ἓν ἀντὶ ἁνάντων οἱ ἄριστοι, κλέος ἀέναον θνητῶν, οἱ δὲ πολλοὶ κεκόρηνται ὅκωσπερ κτήνεα."

"The best choose one thing over all, eternal fame among mortals; but the many are satiated like cattle."

Compare Fr. 81, where he calls the rhetorical method "κοπίδων ἀρχηγός," leader to slaughter. (Allegedly against Pythagoras, see note on Byw. Fr. 138.)

Fragment 55: "Of all things, I prefer those that can be seen, heard, and learned."

An example: "For most people do not understand such things through reflection, nor do they, after perceiving them with their senses, truly comprehend them; instead, they have the illusion that they understand."

The impression of this method on later, somewhat pedantic philosophers is noted by Diogenes Laertius in IX, 8: "But he explains nothing clearly."

Critique of Pure Reason (Kehrbach) p. 177.

The passage from Xenophanes as quoted by Clement of Alexandria in Stromata V, 109, p. 714 P. (Diels Frg. 26):

"But always one remains the same, moving nothing; nor is it fitting for it to change from one state to another."

"φιλεῖ" should not be translated as "loves to conceal itself." The term should not sound so personal. Cf. φιλεῖ in Fr. 87 according to Diels: A hollow person tends to stand rigidly with each word."

The same is expressed by the theory of entropy, a foundation of modern theoretical physics.

It has mostly been understood symbolically: by Lassalle (I p. 114) as a symbol of the Apollonian cult, by Pfleiderer (p. 90) and Schäfer (p. 76) as symbols of cheerful life and death, which is far too sentimental for Heraclitus; on the other hand, as an image of the world process by Bernays (Ges. Abh. I p. 41) and Zeller (I p. 548).

In this sense, especially Schleiermacher and Zeller, who believe that Heraclitus was unable to separate the symbol from the sensory form.

Simpl. in Arist. Phys. 6 a: "Hippasus and Heraclitus made fire the principle..." Zeller (I, p. 541): "the substance in which the principle and essence of all things is sought." Teichmüller (I, p. 135): the fundamental substance "like the air of Anaximenes and the water of Thales." Pfleiderer (p. 119 ff.): "the secondary concrete to the metaphysical ideas." Gomperz, Lassalle, Heinze (Lehre vom Logos, p. 4) also refer to fire as a substance.

The expression ὁδὸς ἄνω κάτω (the way up and down) is used in relation to the visible world: "You see a transformation of bodies and a change of generation, a way up and down, according to Heraclitus..." (Maximus of Tyre, XII, 4 p. 489).

Teichmüller (I p. 137) believes he detects a certain teleology but is unable to prove it.

Plutarch, in "Consolation to Apollonius" 10 (cf. Bernays, Rh. Mus. vol. I, p. 50), presents thoughts aligned with Heraclitus, demonstrating the above perspective:

"These are the same as living and deceased, awake and asleep, new and old; for these, having passed away, are those, and those, having passed away, are these again. Thus nature, from the same substance, once supported our ancestors, then mixed them, generating our fathers, then us, and so on, endlessly cycling others in place of others. And this river of generation flows incessantly, never stopping..."

Fr. 137. Questioned by Diels as a quotation. The focus here is only on the general idea.

Fr. 52. In Lucian's Vita Aucta 14: παῖς παίζων πεσσεύων, συνδιαφερόμενος (Bernays). Zeller sees here an image of the aimlessness of the world-forming power (I, p. 536), Bernays an image of the world's construction and destruction (Rhein. Mus. VIII, p. 112), Teichmüller (II, p. 191 ff.) identifies the effortless, light quality in this conception.

Hi, for several weeks I have been working on a translation of "Der metaphysische Grundgedanke der heraklitischen Philosophie", and I only recently discovered your translation of it. Can I discuss this further with you over direct-message? Thank you!