Plan for a New Atlas of Antiquity — Oswald Spengler

Lecture delivered on October 2, 1924, at the Orientalists' Conference in Munich.

The following draft is not meant to be definitive or perfect but is instead intended to be presented for discussion within academic circles. Aside from the scientific feasibility, which I already consider assured based on initial impressions, the plan also has very serious technical and economic aspects that will not be discussed here.

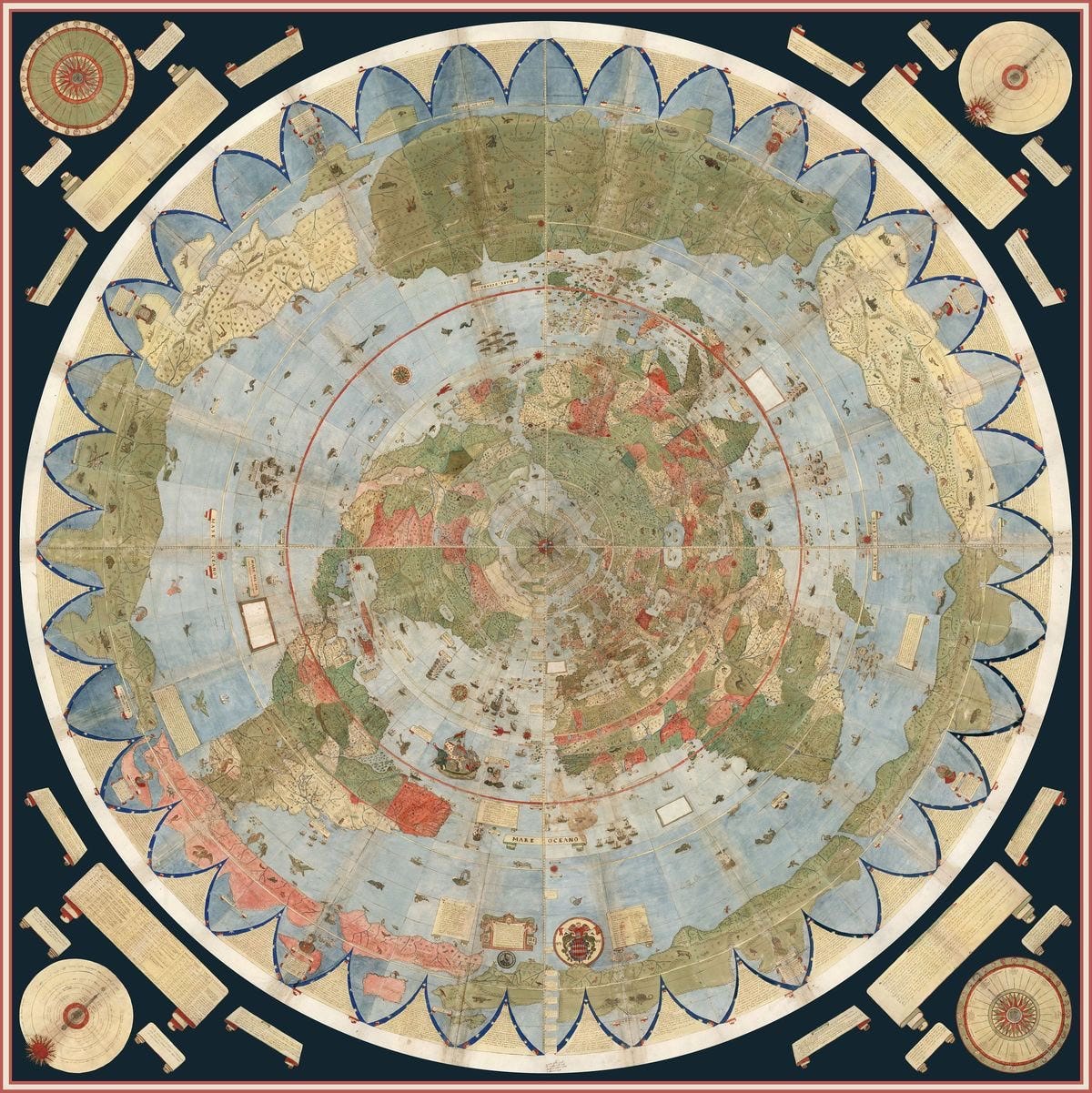

Since historical geography has all but died out in Germany and elsewhere, a deficiency has developed within historical research, along with its consequences, which we are hardly even aware of anymore. The result of any historical research is a historical image, which can be represented visually in cartographic form according to certain ideas. Maps generally disregard personal and unique details, but they emphasize the general form more sharply, allowing for a comprehensive view and understanding at a glance, in a way that no written report, no matter how clear, can achieve. The extent to which this is possible depends significantly on cartographic technique, which has its own foundations, ideas, and ingenious innovations just like any other technique.

It is a fact that the map accompanying our historical research has remained almost unchanged in substance and form for the past 50 years. In older fields such as Greek or Roman history, the map commonly included in a book lags about two generations behind the current state of research. For newer fields—Indian, Chinese, pre-Homeric, Neo-Persian history, etc.—there is no corresponding map at all. For the Aegean world, we still have nothing better than the map that treats the boundaries of Greek dialects as political boundaries, dating from a time when ancient history was a side task of classical philology. The excavations, tomb studies, and comparative ceramics have passed by this image without leaving a trace. The boundaries of the maps are outdated, the drawings are outdated, and the names are outdated.

We have long been accustomed to reading scholarly works about the Etruscans, the Hittites, and pre-dynastic Egypt without knowing how the mentioned places and names relate to each other spatially. As a result, books of this kind often become almost incomprehensible to most readers; they may contain maps of an older style that do not include the mentioned items or hand-drawn sketches that the eye cannot navigate. It often happens that the author himself falls into errors and misjudgments by combining historical facts without being "in the picture" geographically, or that he fails to notice crucial connections altogether. One must take stock of how many areas of current historical research lack a technically detailed map: for India during the Vedic period, for the Homeric period, for Italy during the founding of Rome, for ancient Egypt and Babylon, for the spread of religions and cults during the Roman imperial period. I consider it one of the most urgent tasks of German scholarship to create a new map based on the collective results of scholarly research over the past 50 years, one that adequately expresses historical realities.

But this map must be designed according to entirely different principles. We need new ideas in cartography because we have gained a new perspective on the course and meaning of history. The previous century was content to enter rivers, cities, political boundaries, and names of peoples into the map. Today, we need—within the limits of possibility—first a depiction of the terrain, insofar as it promoted or hindered agriculture, settlement, and transportation at that time; in addition to irrigation and elevation layers, sometimes even the stratification of the soil, the occurrence of metals, and rare stones; ocean currents and wind directions, which channeled early maritime traffic and thus also the migration of peoples. Further, where possible, an indication of the vegetation during the various historical periods. In early times, vast forests were the only decisive obstacle to transportation and migration. In all Nordic languages, "plain" everywhere means "clearing." The sea always connected early cultures and populations; the primeval forest separated them. It is also necessary for the historical map to account for the drying out of increasingly larger areas following the Nordic Ice Age and the subsequent forest and swamp period from the south. As rock carvings teach us, the Sahara emerged scarcely before the 4th millennium. It first began to encroach on Mauretania during Roman times. Spain was then a land of impenetrable forests. A millennium later, the Moors could only prevent desertification through artificial irrigation. But the same applies to Arabia, Babylonia, and Inner Asia. The prehistory of the two oldest cultures did not yet unfold under the impression of the isolation of both river valleys. Without understanding this, one cannot grasp the political prehistory either. Egypt originally had no natural western boundary in the desert.

Furthermore, the most important findings from zoogeography must be included in the map: the distribution of horses, cattle, and lions during different periods. An attempt has recently been made to trace the ancient migrations of the Hamites based on the distribution of African cattle breeds. This is complemented by the inclusion of archaeological finds: burial types, ceramic styles, settlement patterns, and bronze work. Without this, a map of ancient Italy is worthless today. As long as only Etruscans are mentioned and one cannot see on the map the distribution of so-called Etruscan cities by age and location and their burial layers at a glance, the meaning of the Etruscan question will never be found. The map is the only means by which the researcher in a specific field can be presented with the results of all other relevant sciences in a useful and meaningful order.

**Then the Race Question!** It is no longer sufficient to simply print the common names of peoples from various historical periods on top of and alongside one another. A map of ancient Italy or Asia Minor, for example, must include, alongside the distribution of languages and dialects, an indication of the human types (body size, physique, skull shape, facial features) that never align with linguistic boundaries. Only after this, and independently of it, should the historical names of peoples be included, with an indication of their ongoing shifts, replacements, and overlaps. This is already possible with great accuracy in many cases today, especially as one of the most important findings of recent racial research is that many physical traits persistently cling to a land and have repeatedly reasserted themselves despite all migrations since the Stone Age.

It is clear that maps of this style can only be produced through collaboration among representatives from various fields of knowledge. A single individual is no longer up to the task. However, if the geologist, the zoogeographer, and the phytogeographer first create a foundation into which the anthropologist and the prehistorian make their contributions, and finally the political and economic historian takes over, a visual material can be conceived that, by its mere presence, leads to discoveries for the eye that would remain hidden from purely book-based research. Such a project is only possible in Germany today. No other country in the world has such a well-rounded scientific foundation and such mature methods as those presumed here. If internal or external reasons prevent the plan from being realized in Germany, it will never be implemented anywhere else. Finally, historical research will falter over the obstacle posed by the lack of a geographical foundation. The only substantive objection is that research does not yet permit a definitive picture to be drawn. But this finality will never be reached; the picture changes from one generation to the next. If the preliminary picture is not sketched due to unavoidable gaps, then a more mature one will never be possible.

The scope of such a work must be measured quite differently than 50 years ago. Primitive cultures encompass the entire Earth, have used all the seas along the coasts and island chains as intermediaries, and form a living whole with their circles and currents, without which the origin and prehistory of the great cultures cannot be understood. Today, it is no longer possible to find an eastern boundary for so-called classical studies. Questions of the Homeric era extend to the Baltic Sea and the Niger; the world of forms from the migration period cannot be understood without the historical picture of Inner Asia and even China; to Egypt and Babylonia belongs the Stone Age of the northern fringes of the Indian Ocean. On the other hand, the historical boundary upwards can easily be fixed at the Crusades and the Mongol invasion. From that point on, the historical map takes on a different meaning, not intrinsically, but for our practical purposes, and the selection and method of representation accordingly follow a different tendency. Under this premise, a natural grouping of the map material emerges as follows:

1. A group of maps on the primitive world, in its full extent, across all continents, with an overview of all kinds of archaeological finds, metal deposits, and the trade routes of ancient commerce and later migrations that trace along them, with the distribution areas of religious, social, economic, and political basic forms. Such a map, by its mere existence, simplifies and resolves a whole series of problems from the earliest history. For instance, individual adventurers can penetrate wherever they wish, but entire tribes always follow a known path secured by the inhabitants in terms of provisions and loot, and therefore geographically identifiable from the plant world and settlement patterns.

2. A combined group should cover the fates of Egypt and Babylonia and the surrounding world,** starting from the earliest times of stoneworking and the Sahara, still covered in plants, and ending around the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. Here we need overviews of ethnographic divisions, the districts of Egypt, and the Sumerian principalities, the geographical distribution of cults and gods, the shifting political centers of gravity over time, and the deep connections from the Indian Ocean to deep within the northern landmass.

3. The Near Eastern world between Cyrene and Iran, the Black Sea, and southern Arabia, from 1500 BC to the Persian period.** Here fall the great streams of peoples from the vast inland regions of the north, which fundamentally altered the character and spirit of this landscape. We have today the results of excavations from Boghazköy and Amarna, Troy and the earliest Italy, the findings of comparative onomastics, cuneiform, and hieroglyphic literature, but we have nothing that could be called a representation of these results in map form. And it is precisely here that we stumble in the dark due to the lack of visual summaries, overlooking obvious discoveries, and allowing errors to grow old that the first map would never have allowed to arise.

4. The Indian world. Here, decisive discoveries are to be expected as soon as the results of the until now purely literary research are combined with those of the rapidly growing archaeological finds. The distribution and stratification of graves, weapons, and pottery forms must, once they are visually presented to the Indologist, change the entire structure of Indian history, give an idea of Dravidian culture, and thereby first illuminate the fates of the oldest Aryan world. However, I have not come across even a hint of a map of ancient India.

5. The ancient Chinese culture: Recently, some attempts have been made to geographically establish the earliest state world on the Yellow River based on historical sources. Had this been done earlier, the concept of ancient China would not still be emotionally equated with the current country, thereby casting the entire history in a false light. The state world of the early Zhou period was as small and complex as that of Homeric Greece. All these tiny states could be packed into an area the size of southern Germany, and the principalities of the earliest Vedic period were certainly no larger.

6. A cartographic depiction of the two ancient American cultures: The first inadequate attempts have been made.

7. The pre-classical world of the entire Mediterranean in the 2nd millennium BC: This extends down to Homer, with the paths of the Sea Peoples, who pushed against Egypt in the 14th and 13th centuries, and with the circles and layers of Iberian, partly deep African, Sardinian, Etruscan, Libyan, Minoan, and Mycenaean forms. The connections extend to the rock carvings of Scandinavia and the finds in Sudan, Nubia, and southern Arabia. Here lie the prerequisites for the later structure of the classical world, which has so far been reconstructed backward from written sources and thus primarily philologically.

8. The classical world itself up to the Migration Period: Its geographical image needs to be completely redrawn. We must finally see how not only the physical appearance of the population but also its density and political significance shifts, how certain core areas of Homeric culture—Thessaly, for instance—recede, while others—Latium—rise to prominence, how important cities become villages, and villages become cities. We must finally—here and elsewhere—make visible the deep inner difference between fortress, settlement, market, city, trading place, provincial, major, and global city; between tribe, people, nation; and between landscape, territory, and state. The name Etruscan, and likewise the names Hellene, Roman, Ionian, and Italic, designate something different in each century. The era of city formation around 800 BC and the dissolution of city-states into great powers around 300 BC must be developmentally portrayed in images, as must the racial conditions down to the Imperial period, where the population of individual provinces is still simply referred to by their names today, instead of by dialect, acceptance or rejection of certain cults, the disappearance or increase of the rural population, and the concentration or reduction of medium-sized cities. It is widely discernible where the valley areas have a different human type than the mountainous regions, where the pre-Indo-European population has remained en masse. This, in turn, explains the movement of the Germanic tribes: where they settle en masse and displace the natives, where they merely sit as lords over a layer of serfs, and where they only exercise formal rule. Only by seeing this can we understand the formation of the new nations and their languages, the longer duration or rapid collapse of Germanic kingdoms—the Gothic rule in Italy also failed to take root largely because there were no large river valleys south of the Apennines, while the Visigothic kingdom in Spain sat on the plateau like a fortress.

9. The darkest area of history and geography: The Middle East from Alexander the Great to the Mongol invasion. We have nothing that gives us a clear picture of Byzantium, such as the linguistic, social, and religious stratification of Asia Minor, Syria, and Egypt under Justinian. The Sassanian Empire, a crucial creation at the crossroads of four high cultures, is still a formless concept to us today. Aside from the spread of Christianity in the Roman Empire, we don't even have an attempt to trace the spread of new religions after the birth of Christ, such as the Jewish Talmudic, Persian, Manichaean, and later Nestorian religions, or the spread of so-called late antique cults of Sol and Mithras as far as Portugal and Inner Asia. We do not see in the image how these religious communities become nations that dissolve the older states; how these nations, in part, have their center of gravity in certain landscapes, where they absorb the racial characteristics of those regions until the storm of Islam, whose depiction in map form has also not been attempted, finally incorporates most of these nations—and therefore religions. This group of maps would show that it is again the ancient trade and migration routes, already indicated by Stone Age finds, along which the spread of the great missionary religions now moves.

10. Finally, a group of maps is needed: This would summarize Asia and Europe around 1000 AD as a unified area. It begins with the Migration Period, which shakes the lands from the Chinese border to Spain and North Africa and spreads a new series of political forms over this vast stretch, and concludes in the far west with the era of the Crusades, from which emerges the state world of a new culture, and from there, along the vast ancient southern border of the Stone Age northern circle, which now forms a boundary between forest and desert, through the Mongol invasion, which transforms all of Asia, including Russia, into an area where the ruins of ancient cultures are overlaid by shifting zones of power of various conquerors and tribes with their followers. From here on, the creative history of the world is essentially Western, i.e., our own history.